Hunt for cloud session anomalies with Cloud SIEM

In today’s cloud-native world, systems are usually accessed by users from multiple devices and in various geographic locations. Anyone who has tried to operationalize an impossible travel type alert for cloud resources will understand the myriad nuances and gotchas involved in such an endeavor.

A user may be accessing a cloud resource from a mobile device that is tied to a carrier network well away from their normal geographic location. Likewise, users may be accessing cloud resources from endpoints that are also located in the cloud and are geographically dispersed. Indeed, the cloud makes the impossible very much possible within the context of an impossible travel alert.

In addition to these dynamics, token, cookie or other forms of credential theft such as phishing are all techniques that threat actors use to gain unauthorized access to cloud resources.

The threat labs team has authored blog posts on how to protect against cloud credential theft on both Windows and Linux endpoints. However, we need to take this dynamic further - or, better put, upwards - and look at how cloud telemetry can aid in the detection of anomalous user sessions.

What are session anomalies?

According to MITRE - the definition of a session is a temporary and interactive information interchange between two or more devices communicating over a network.

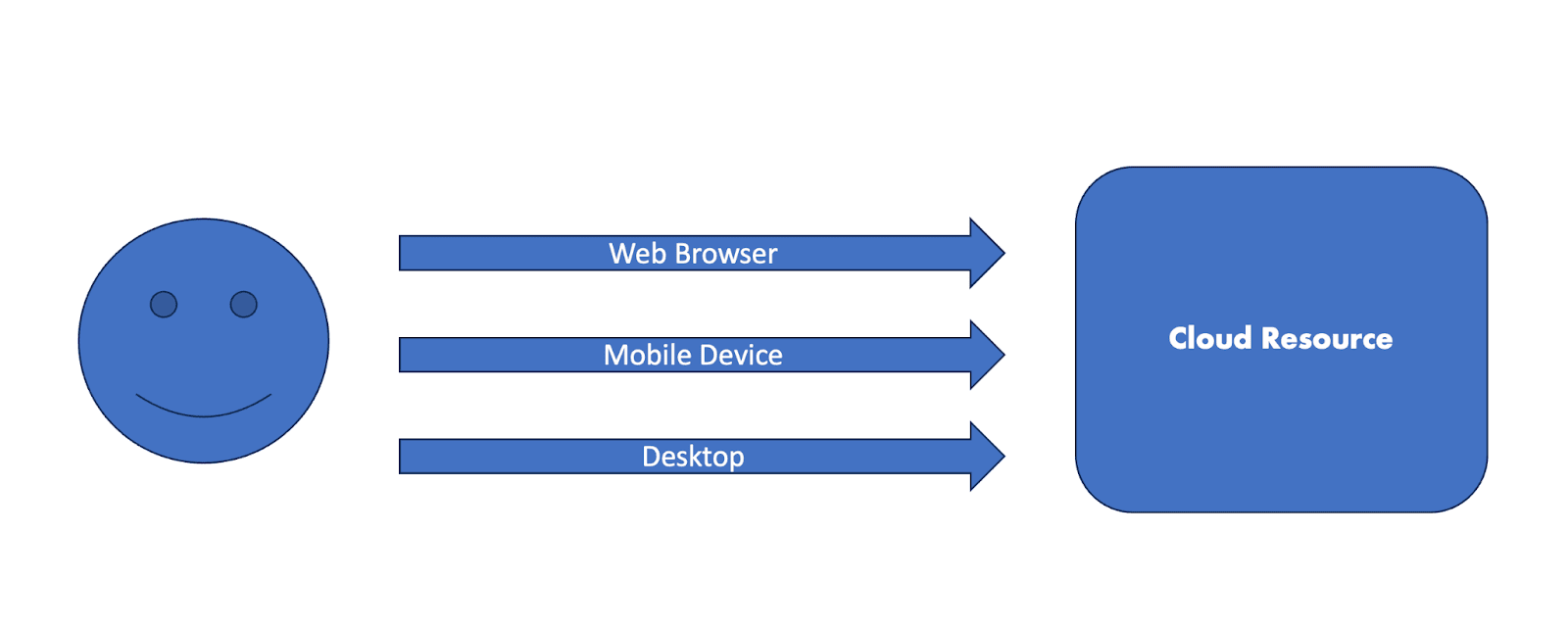

If we look at this definition through a cloud lens, we can visualize a very simplified normal session flow like this:

A user utilizes a web browser, mobile device or desktop/laptop computer to access various cloud resources such as SaaS applications, IaaS or PaaS platforms or even other cloud-based storage.

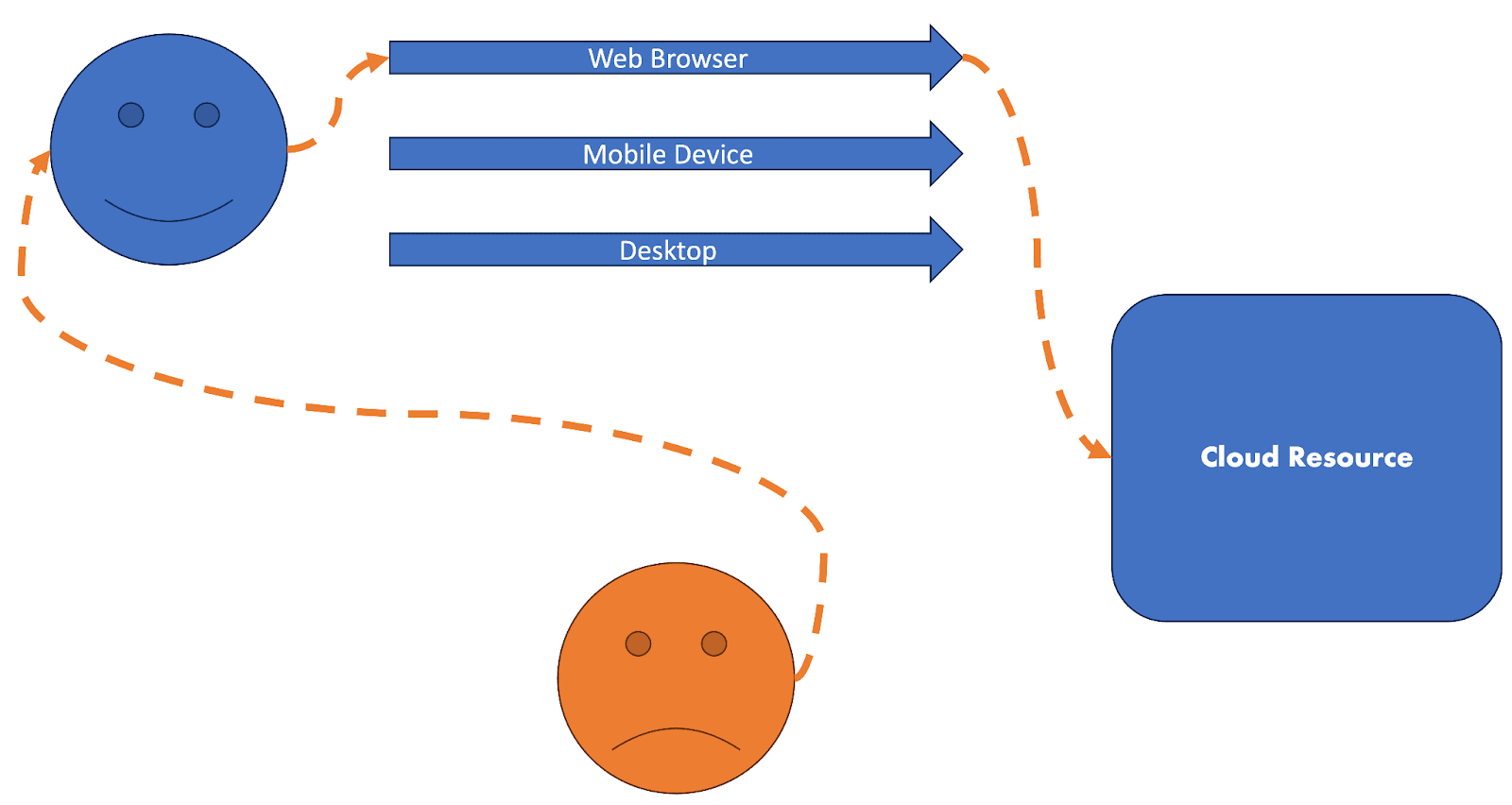

Now let us consider the following scenario: our happy user receives a convincing phishing email and their cloud session is stolen via an adversary-in-the-middle technique.

We now have the dynamic of an anomalous session coming into focus as there is now one invalid and unauthorized user utilizing the session of a valid and authorized user.

How do we tackle the problem of hunting or alerting on this activity in our environments?

Session anomaly hunting

Now that we know what a normal session looks like versus an abnormal or perhaps malicious session, we can start to build out some hypotheses for hunting and alerting.

To build on this, let’s lay out a few hypotheses for what anomalous sessions might look like in our environments:

- A stolen session will potentially utilize multiple IP addresses / ASNs associated with the same username

- A stolen session will result in potentially multiple User Agents in use by a single username

- A stolen session might occur from an IP address not previously seen in the environment

- A stolen session might result in multiple geographic locations in use by a single user

- A stolen session might result in logins from geographic locations not previously seen in the environment

- A stolen session might result in user actions not typically performed in a normal fashion by the user

With these hypotheses in mind, let’s take a look at some cloud telemetry and look at some queries and rules that may help us detect this activity.

Entra ID

To begin testing some of our above hypotheses, we can use Azure Active Directory / Entra ID telemetry. We can start with a query that looks at normalized and enriched data from Cloud SIEM:

_index=sec_record_authentication

| where metadata_deviceEventId = "SignInLogs"

| where errorCode = "0"

| timeslice 1d

| count_distinct(device_ip_asn) as distinct_asns, values(device_ip_asn) as asns by user_username, _timesliceIn this query, we are:

- Looking at successful authentications from Entra ID SignInLogs

- Timeslicing the data into 1-day intervals

- Counting the number of distinct ASNs in use by a particular user, grouped by our timeslice

- Displaying the ASN values, also grouped by the user and timeslice

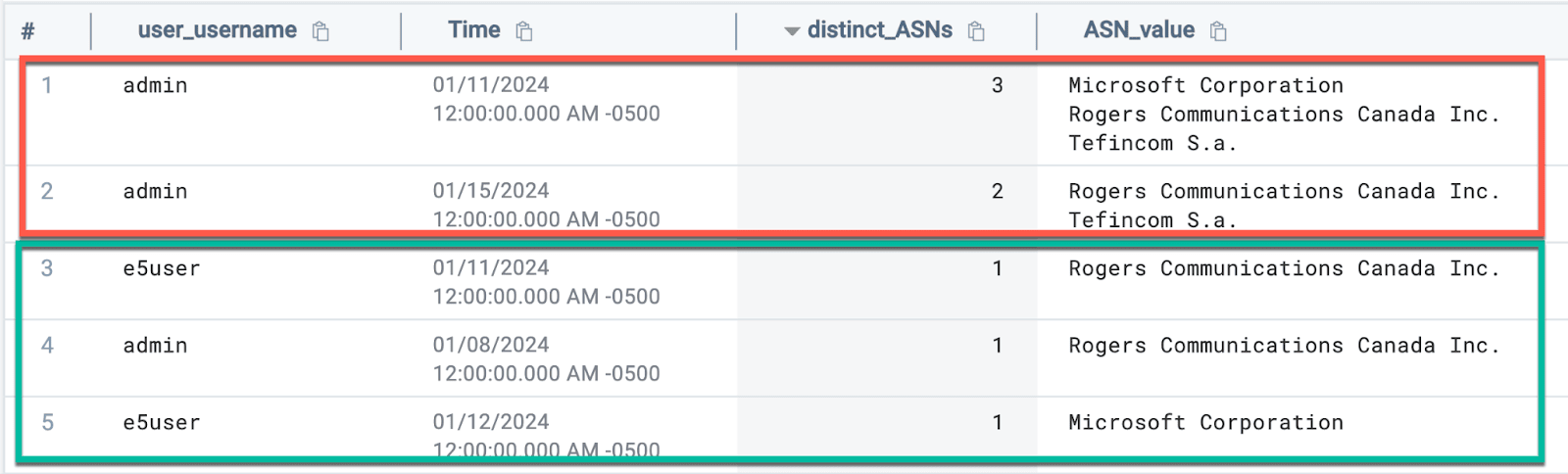

Looking at our results, we see an interesting pattern emerge:

We can see the events highlighted in green have 1 distinct ASN in use per user. However, when we look at events highlighted in red, we can see that there are multiple ASNs in use for a single user in a single day.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that a session was stolen, but it does give us a thread to pull on. Let’s refine our query and add some additional context:

_index=sec_record_authentication

| where metadata_deviceEventId = "SignInLogs"

| where errorCode = "0"

| timeslice 1d

| count_distinct(device_ip_asn) as distinct_asns, values(device_ip_asn) as asns, count_distinct(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) as distinct_countries, values(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) as countries by user_username, _timeslice

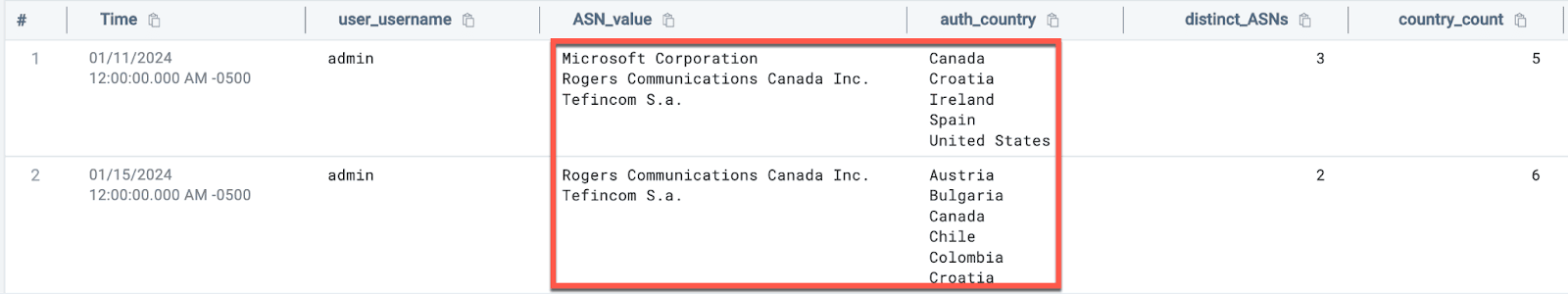

| where distinct_asns > 1 AND distinct_countries > 2This query is adding a few elements to the query that we used above, namely:

- Counting the number of distinct countries in use by a user in a particular timeslice

- Adding a filter at the end to return results when multiple ASNs are in use AND more than two countries are present

And looking at the results, we can see that something suspicious is occurring with our admin account:

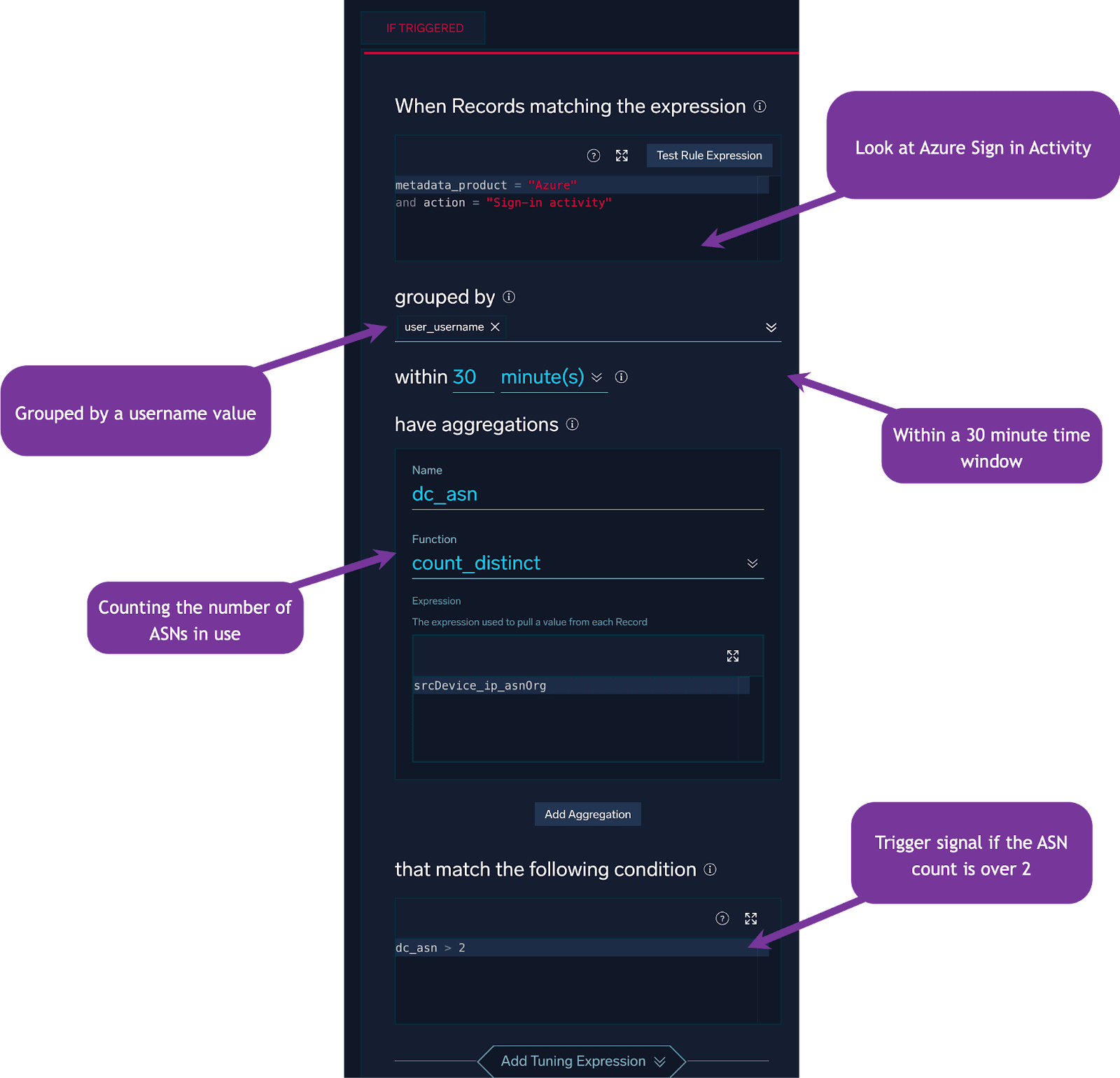

Another approach to the above detection dynamics is a Cloud SIEM Aggregation rule.

We can craft an aggregation rule that looks for a user utilizing more than a certain number of ASNs in a given time period:

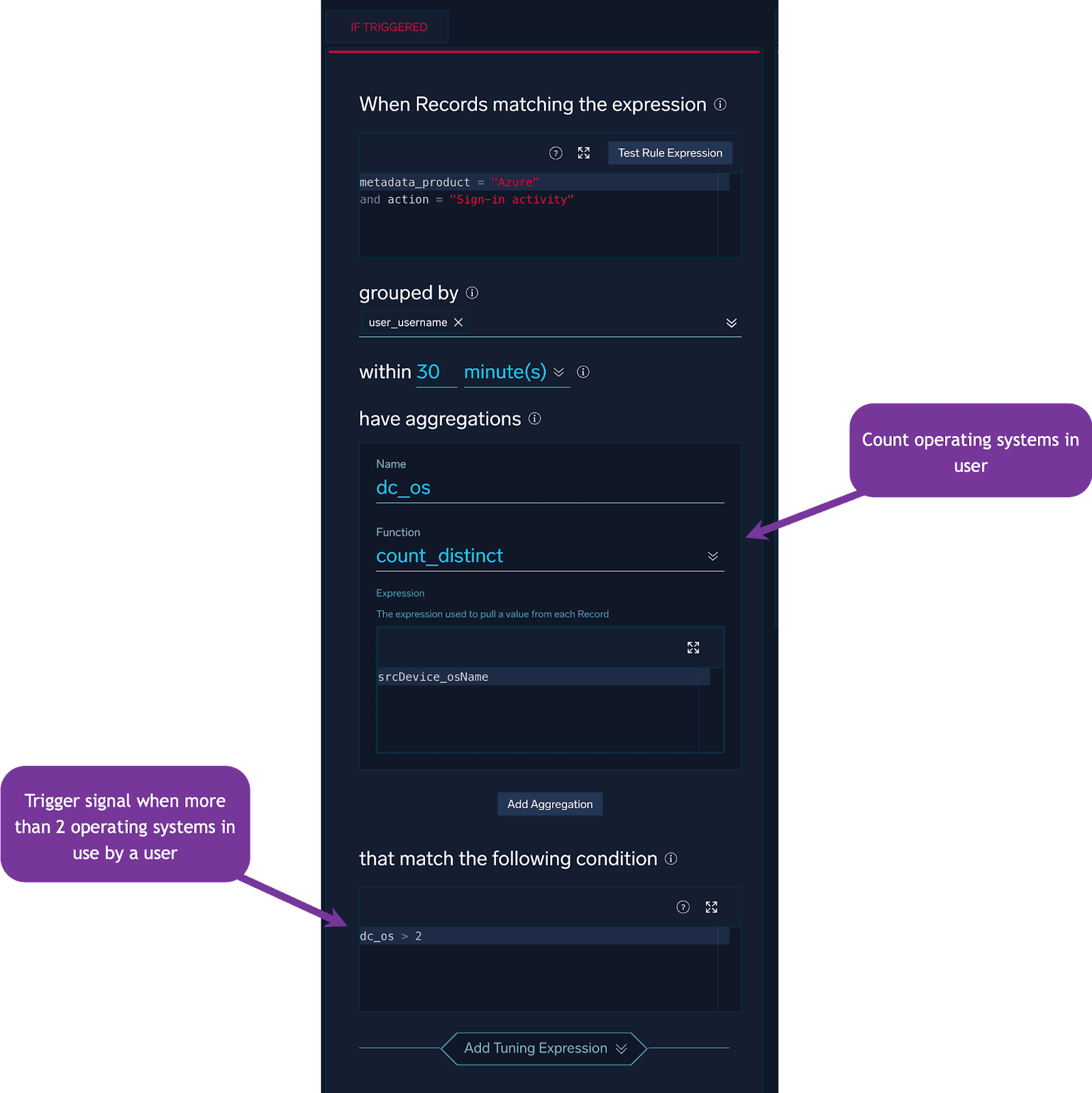

In addition to applying this detection approach to ASN values, we can also utilize the Operating System field:

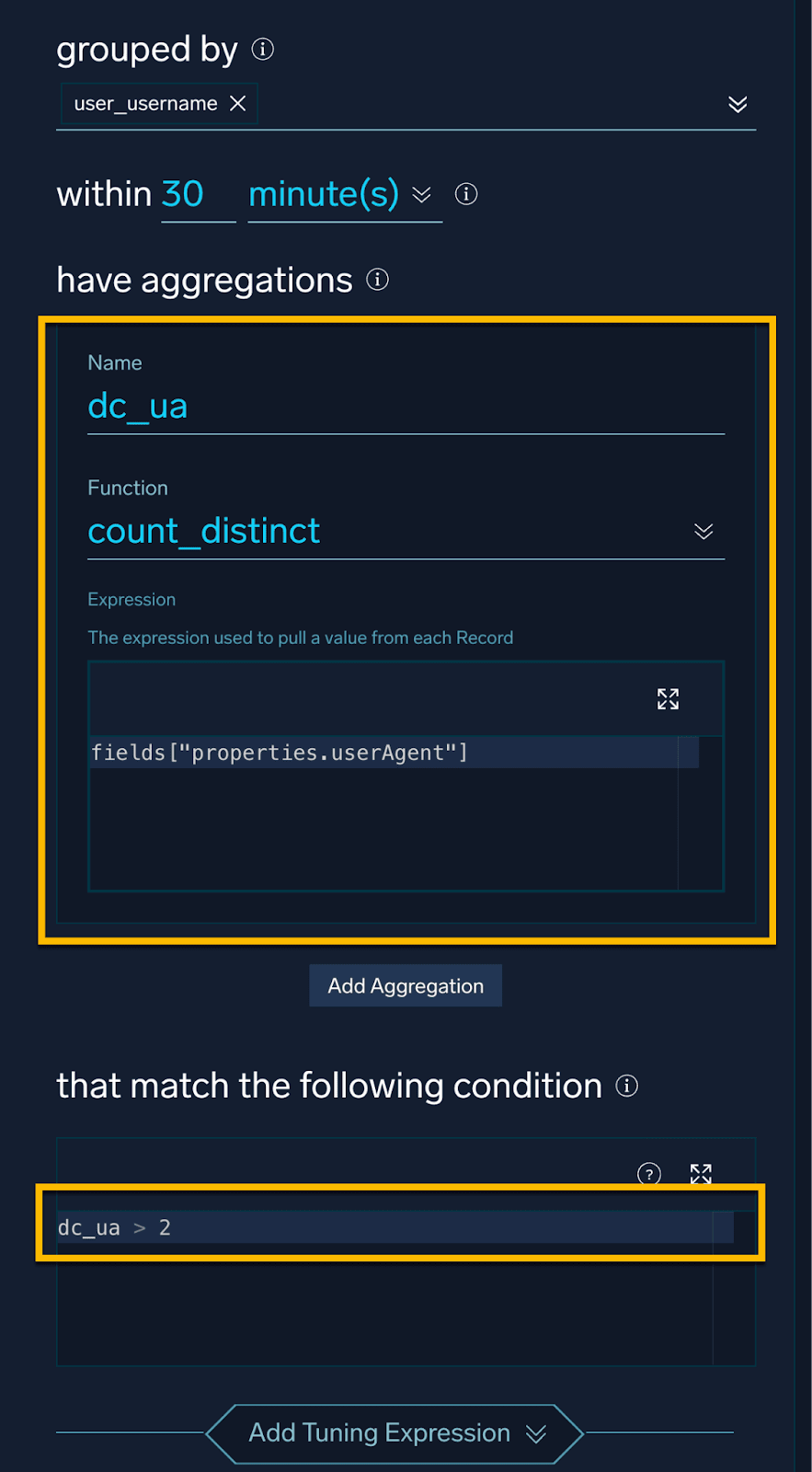

And for User Agents, the logic will look very similar, but with a different count:

These approaches are all great, but the keen-eyed among you might have noticed that we are using static thresholds for our detection. These thresholds may be too sensitive or not sensitive enough for your environment.

What if we did not want to set a static value for these thresholds, but wanted to baseline this type of activity and alert on deviations from the baseline automatically?

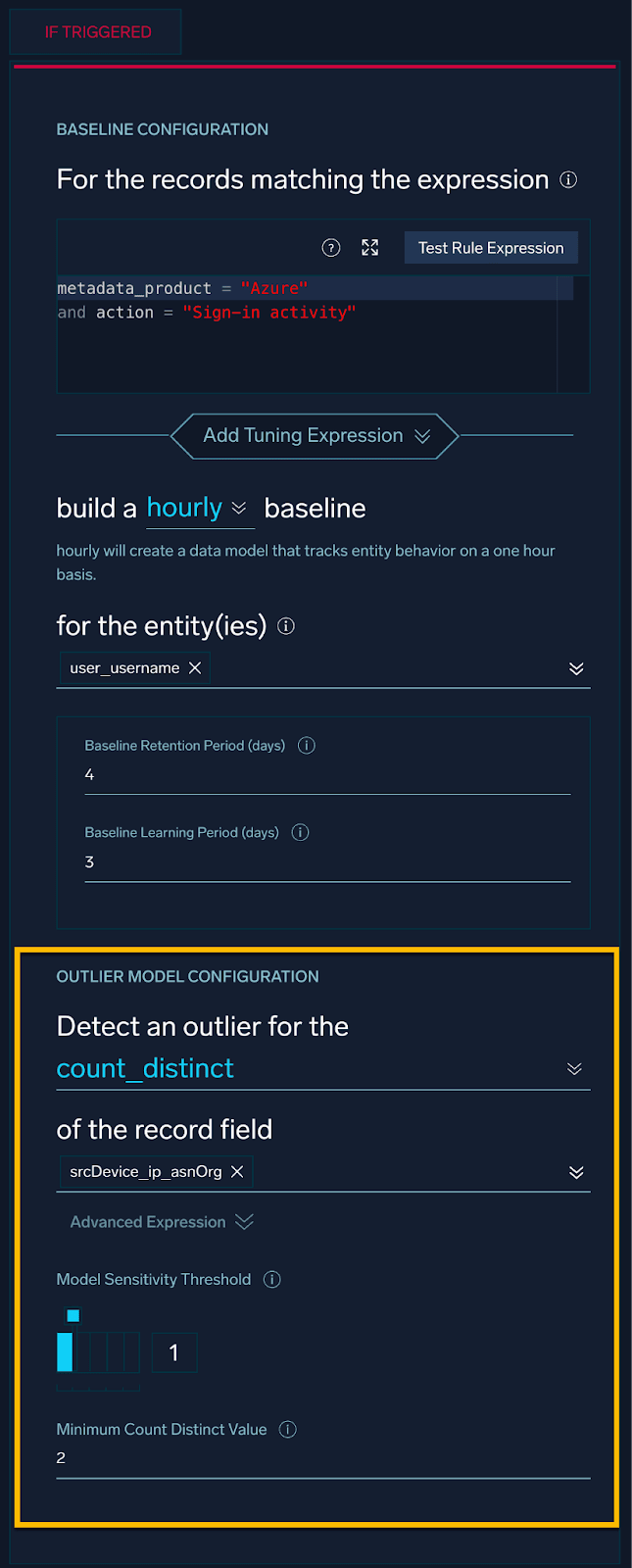

That is the exact use case for Cloud SIEM Outlier Rules. When using Outlier Rules, we no longer need to define a static value for the thresholds. Instead, the rule will automatically baseline the activity and alert on deviations from the baseline.

This rule will baseline Azure signin activity and will build an hourly baseline of distinct counts of ASNs in use by a particular user. When the number of ASNs in use exceeds the baseline by a certain number of standard deviations, the rule will alert.

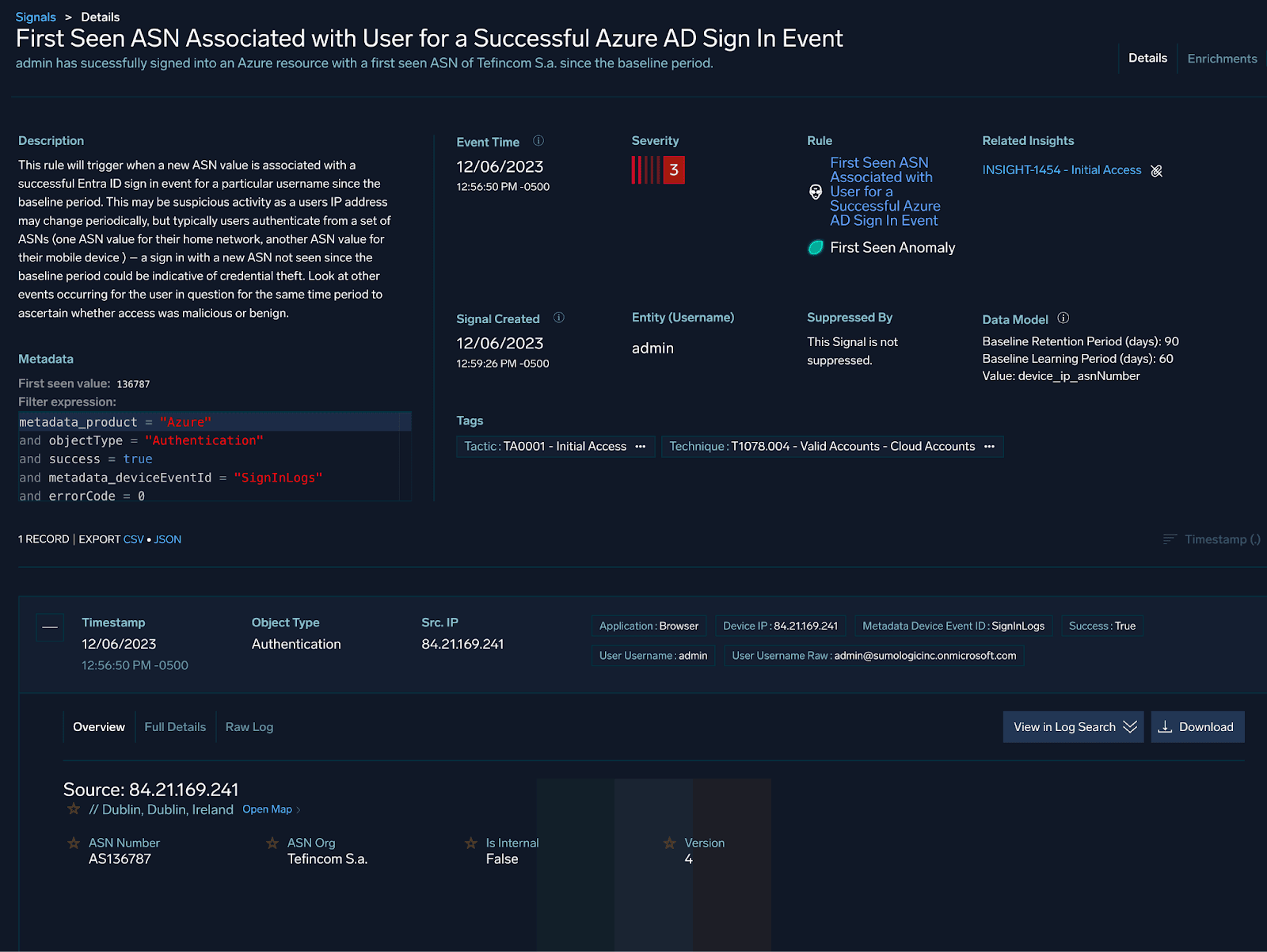

Our alert for the outlier rule will look something like:

As is typical with these types of alerts, an analyst will most likely want to compare current activity to historical activity for the user in question.

The party does not stop here, and we can also use UEBA and First Seen rules to flag on successful authentications to our cloud resources from ASNs not previously seen in the baseline.

AWS Elastic Kubernetes Service

We can also apply the detection and hunting approaches outlined thus far to AWS Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) telemetry.

Consider the following scenario: an AWS access key and secret are stolen by a threat actor; the stolen credentials are used to access an EKS cluster from a different IP address than the legitimate user.

We can look at the following query to help detect this activity:

_collector="tr-eks-cloudwatch"

| json field=_raw "message.userAgent" as user_agent

| json "message.user.extra.arn[0]" as arn

| json "message.sourceIPs[0]" as src_ip

| json field=_raw "message.user.extra.accessKeyId[0]" as key_id

| isPublicIP(src_ip) as isPublic

| where isPublic = true

| values(src_ip) as src_ips by arn, key_id, user_agentIn this query, we are:

- Parsing out the user agent, AWS ARN, AWS Key ID and source IP fields

- Displaying results only if the source IP accessing our cluster is a public IP

- Displaying the corresponding source IPs sorted by the ARN, key id and user agent fields

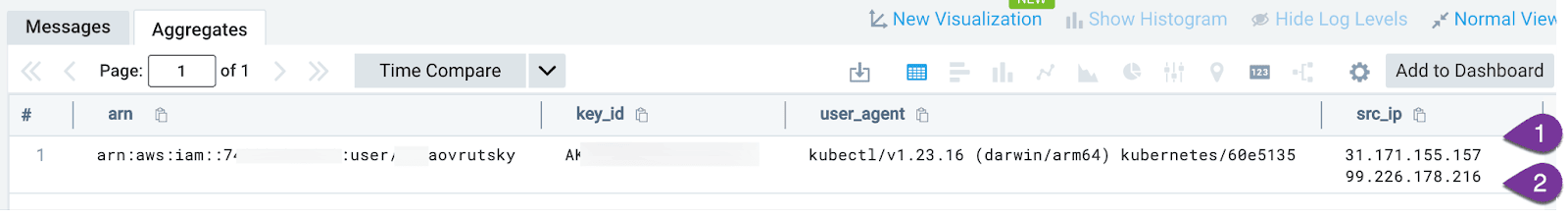

Looking at the results, we can see that in this case, the same ARN / key and user agent combination is being used from multiple public IP addresses:

Kubernetes workloads present interesting challenges to defenders as there are many layers of telemetry that need to be collected and correlated in order to get a full picture of what is happening.

In our example above, the session anomaly occurred due to stolen AWS keys. However, Kubernetes credentials can also be stolen from kubeconfig files on developer workstations or from CI/CD pipelines.

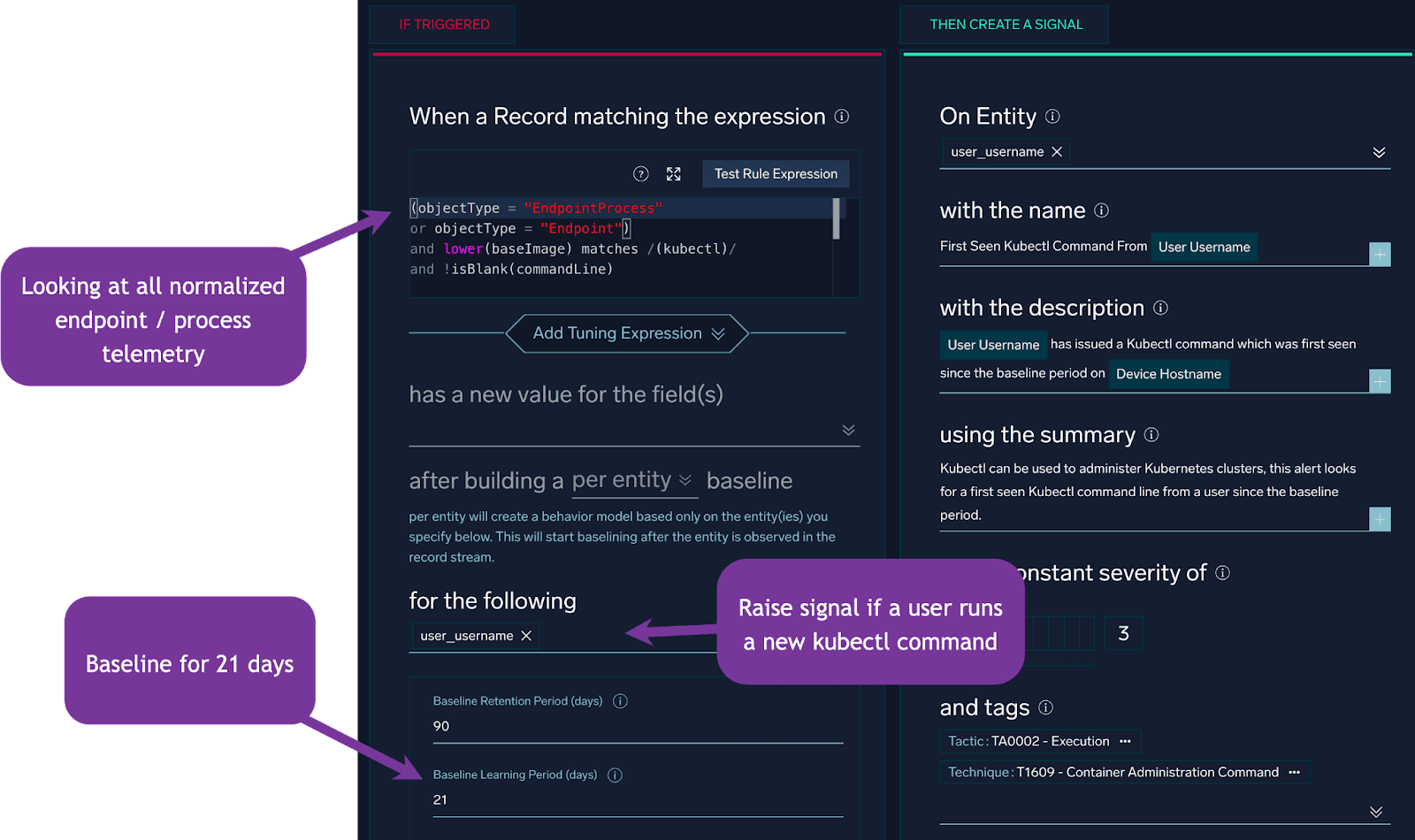

Adding to this challenge is the fact that the Kubectl binary itself can be executed from either a Linux or Windows endpoint. This means that defenders need to have visibility into both Linux and Windows endpoint telemetry in order to detect this activity.

The challenges of “clean data” as well as baselining are aided by Cloud SIEM’s normalization features and first seen rules.

The rule itself will look like:

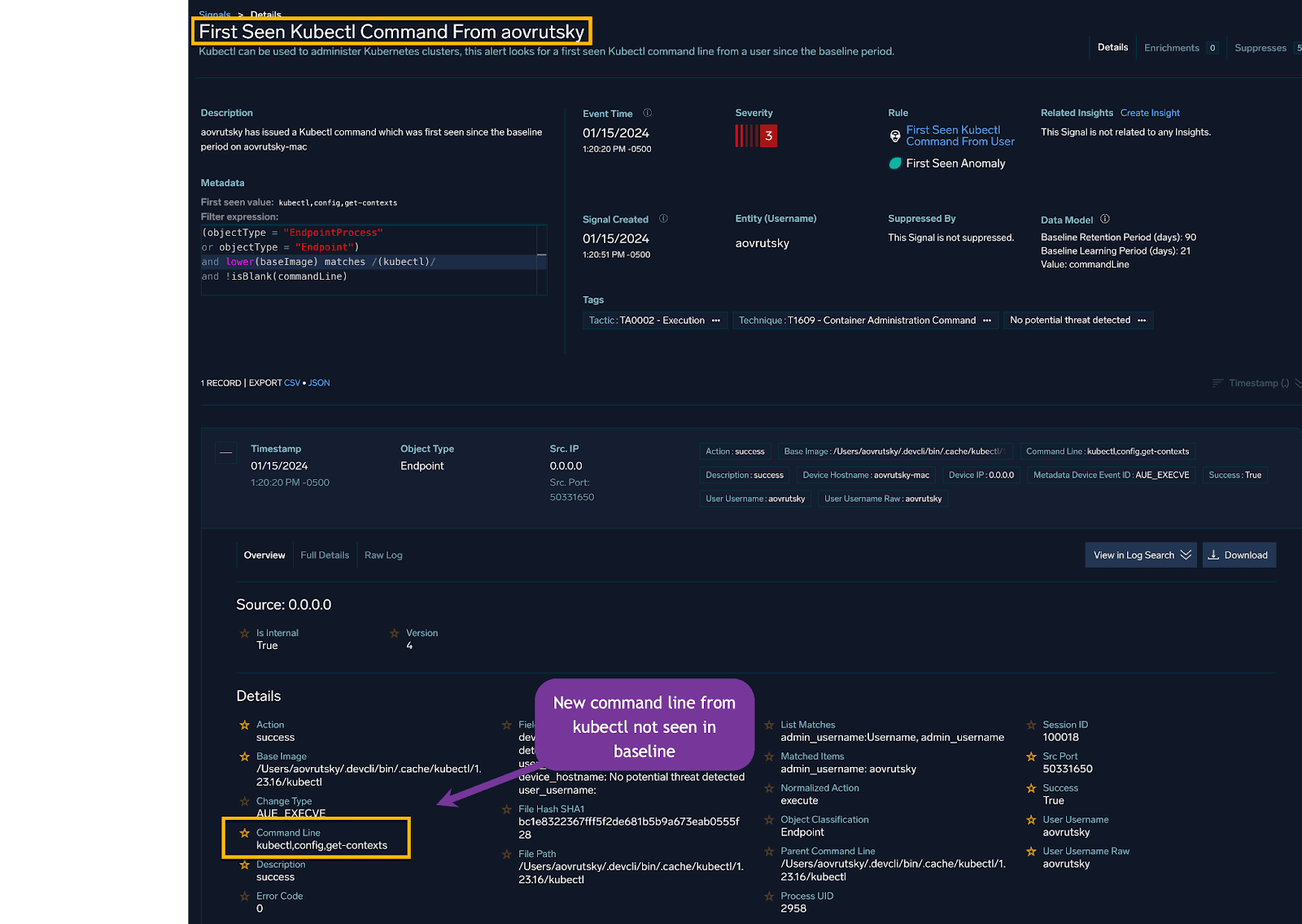

And the resulting Cloud SIEM signal will look like:

We can see that in this case, a user ran a kubectl command line of: “kubectl config get-contexts” which was not previously seen in the baseline.

In this particular Signal, the telemetry used stemmed from Jamf. However, regardless of the source, the normalization features of Cloud SIEM allow us to write rules that are agnostic to the source of the telemetry.

Okta

Our threat hunting and detection hypotheses outlined earlier can also be applied to Okta telemetry. Let’s take a look at some examples.

In our first example, we’ll be looking at a user accessing applications that are behind Okta single sign-on (SSO) with multiple User Agents in a short time period.

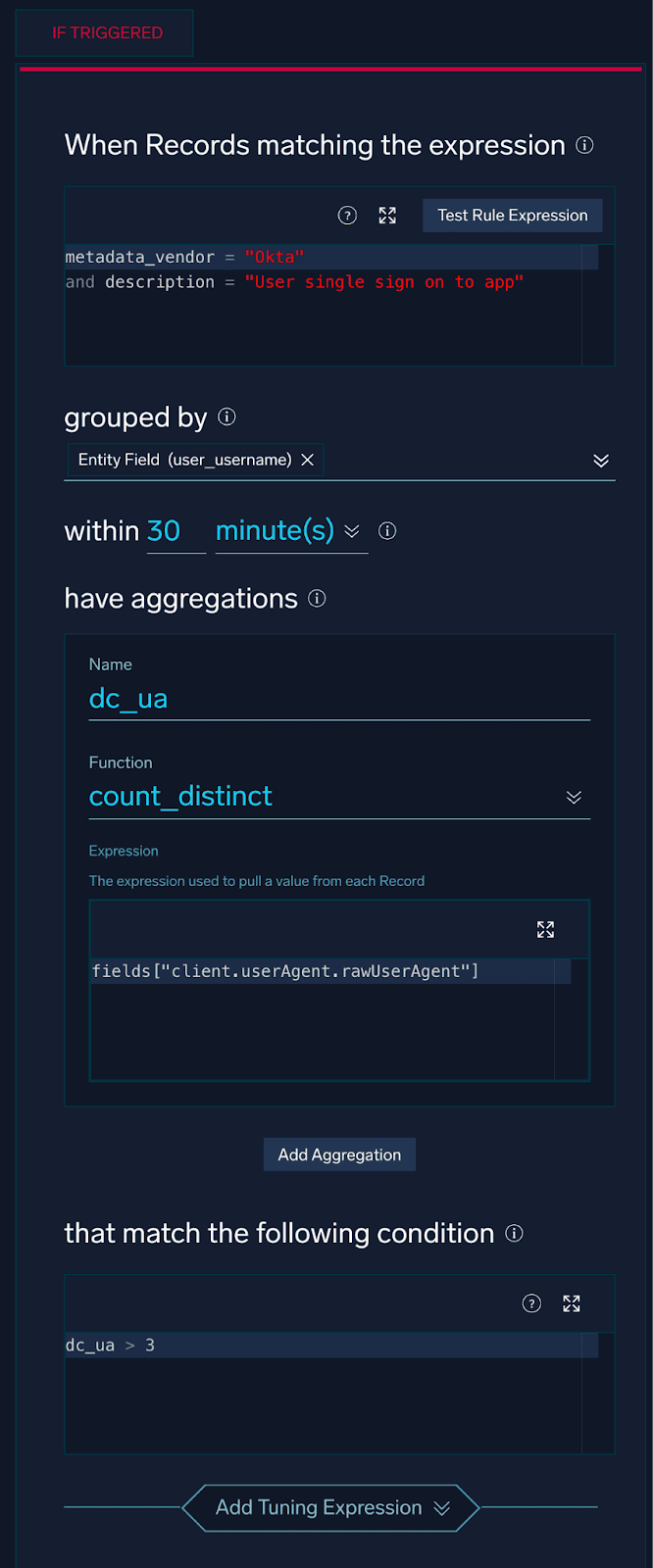

In Cloud SIEM, this rule logic will look like this:

Because every network is different, with different authentication patterns and different developer workloads, it is important to baseline this type of activity before alerting on it.

We can look at a query like the one below to get an idea of how many User Agents are in use by a particular user in a particular time period:

_index=sec_record_authentication

| where metadata_vendor == "Okta" and description == "User single sign on to app"

| where !isBlank(http_userAgent)

| timeslice 1h

| values(http_userAgent) as user_agents, count_distinct(http_userAgent) as distinct_user_agents by user_username, _timeslice

| where distinct_user_agents > 3

| sort by distinct_user_agents descAnd looking at our results, we can start to see some interesting patterns emerge:

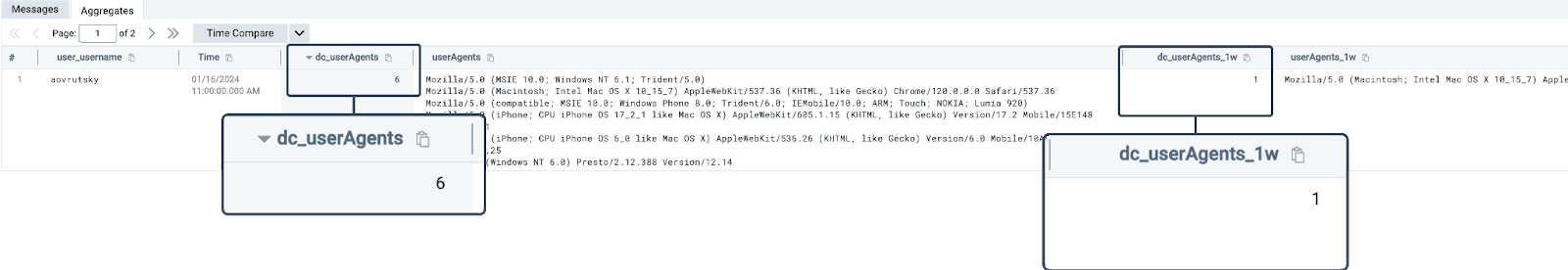

We see that, within an hour time frame for our query, a user has used six distinct User Agents.

We can then compare this current usage to historical usage by utilizing the compare operator. We can see that this user’s current behavior is significantly different from their historical behavior.

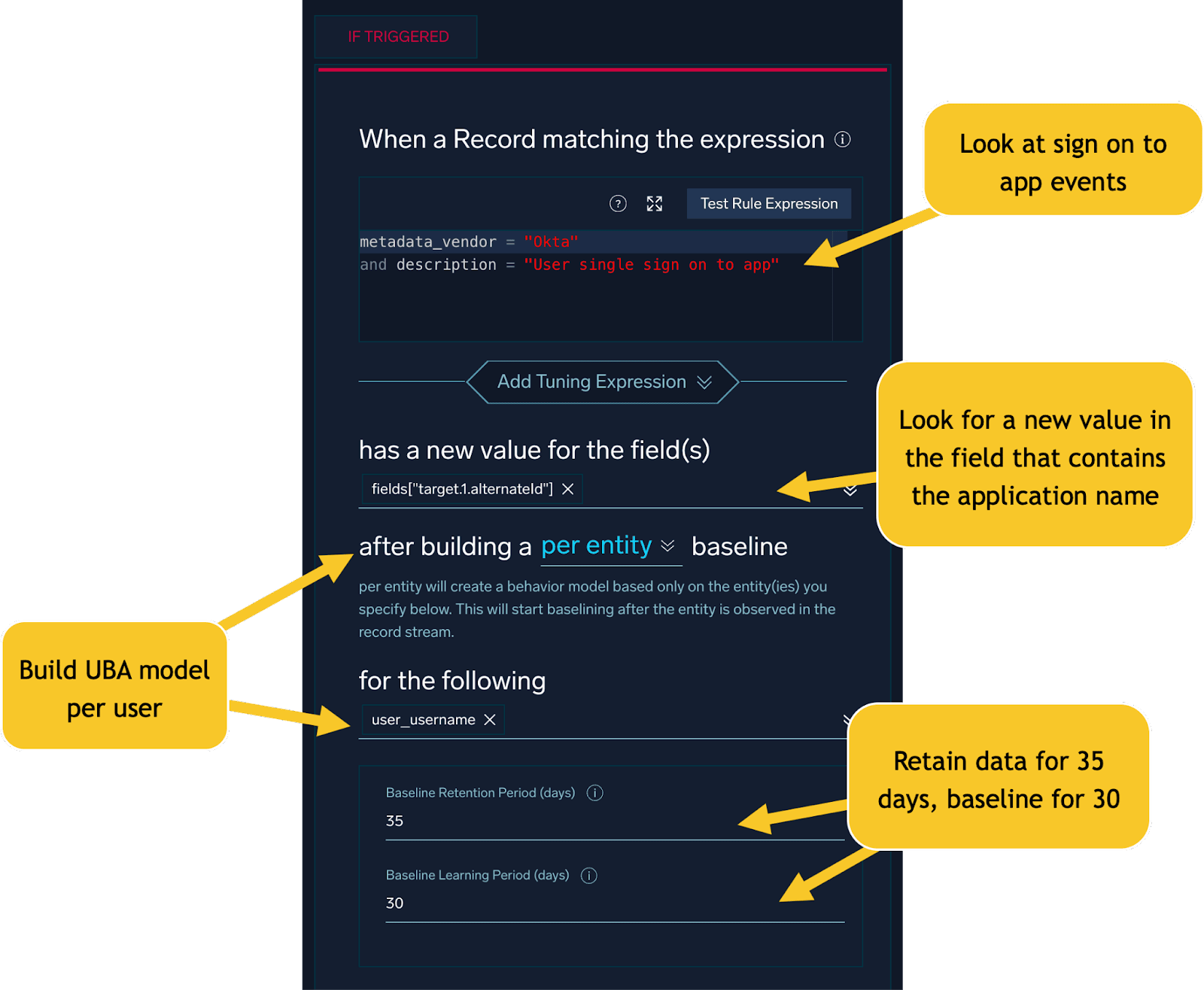

In addition to authentication-level anomalies, we can also look for suspicious access patterns that may indicate a stolen session.

A good example here is a user accessing an application behind Okta SSO not previously seen in the baseline:

When such alerts or Signals are received, analysts will need to pivot off user name, application, IP address, and User Agent to determine if the activity is legitimate or malicious.

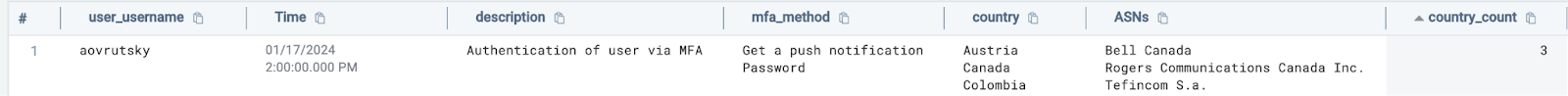

One way that we can perform deeper investigations into suspicious Okta events is by looking at whether the user performed multi-factor authentication from different geographic locations:

_index=sec_record_authentication

| where metadata_vendor = "Okta"

| where description = "Authentication of user via MFA"

| where !isBlank(srcDevice_ip_countryCode)

| timeslice 1h

| values(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) as countries, values(description) as descriptions, values(%"fields.target.2.detailentry.methodtypeused") as mfa_methods by user_username, _timeslice

| where count_distinct(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) > 1

| sort by _timeslice descLooking at the results, we see our user performing multi factor authentication from different countries:

The “Get a push notification” event corresponds to a user accepting a push notification and the password verify event corresponds to a user entering their password. If we see these events from different countries in a short time period, this is a strong indicator of a stolen session.

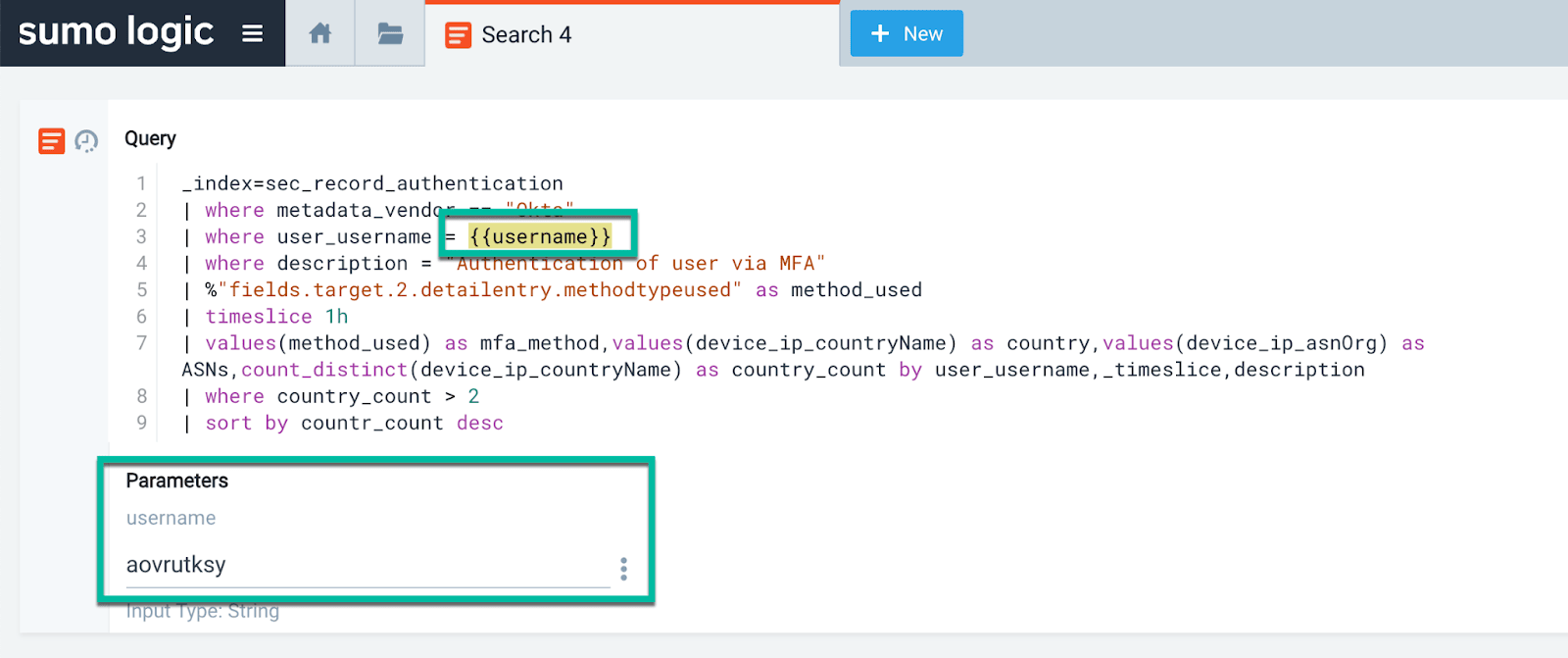

To make things easier for analysts, we can use a parameterized query:

_index=sec_record_authentication

| where metadata_vendor == "Okta"

| where user_username = {{username}}

| where description = "Authentication of user via MFA"

| where !isBlank(%"fields.target.2.detailentry.methodtypeused")

| timeslice 1h

| values(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) as countries, values(mfa_method) as mfa_methods by _timeslice

| sort by _timeslice descWhich will generate an input box to make editing the query much less cumbersome:

Amazon Web Services (AWS)

We’ve been making our way through some of the hunting hypotheses outlined at the start of this blog, and now we’ll take a look at AWS CloudTrail telemetry.

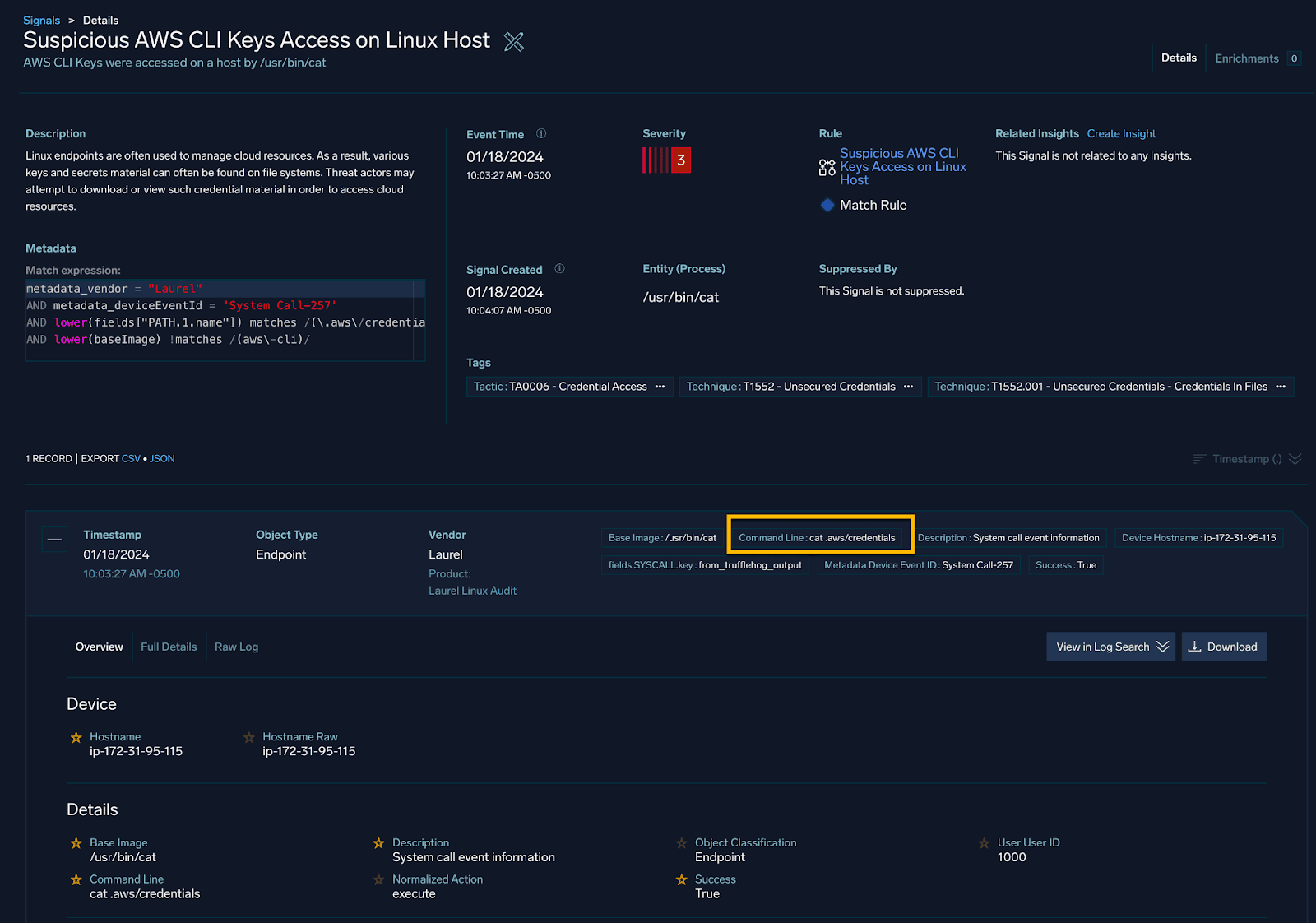

Let’s imagine a scenario where an analyst is looking at the following Cloud SIEM signal:

This Signal conveys that someone on a Linux host ran the command: “cat .aws/credentials” in order to read the AWS credential file.

As a next step, the analyst must figure out if this action was malicious or intended. The analyst can look at the CloudTrail telemetry to see if the access key in question was used from multiple IP addresses or ASNs.

We can look at the following query:

_index=sec_record_audit

| where metadata_product = "CloudTrail"

| where %"fields.userIdentity.accessKeyId" = "{{access_key_id}}" and !isBlank(device_ip_asn)

| timeslice 1h

| values(device_ip_asn) as asns, values(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) as countries, values(http_userAgent) as user_agents by _timeslice

| where count_distinct(device_ip_asn) > 1 AND count_distinct(srcDevice_ip_countryCode) > 1In this query we are looking at CloudTrail telemetry and are timeslicing our data and looking for a particular access key being used from multiple ASNs and countries.

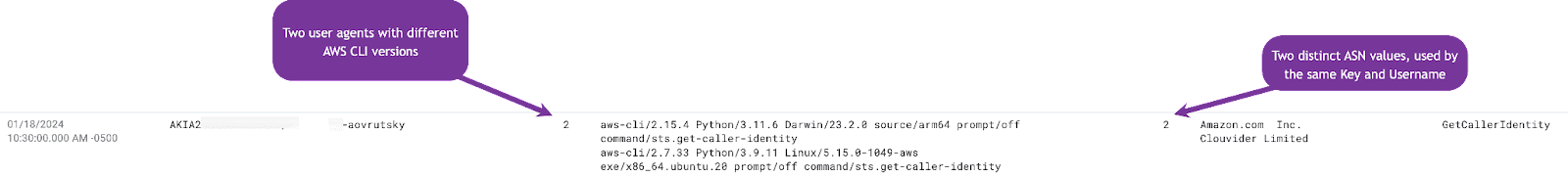

Looking at our results, we see an interesting dynamic emerge:

In this case, we can see that the potentially stolen access key was used from two different ASNs as well as two different countries. This is a strong indicator that the access key was stolen and is being used by a threat actor.

Another way to approach this kind of threat hunt is to build a “session profile” for a given user. In this approach, we can use the ASN, geolocation, User Agent and username to build a profile of what a normal session looks like for a particular user.

In query form, this will look something like:

_index=sec_record_audit

| where metadata_product = "CloudTrail"

| where !isBlank(user_username) and !isBlank(device_ip_asn)

// Make an authentication profile consisting of ASN, Country, User Agent and Username

| concat(device_ip_asn, ",", srcDevice_ip_countryCode, ",", http_userAgent, ",", user_username) as session_profile

// Find the least common patterns in the authentication profile

| logreduce by session_profile

| where _count < 10In this query, we are using the concat operator in order to build a field called “session_profile” we are then using LogReduce to find the least common patterns in the session profile.

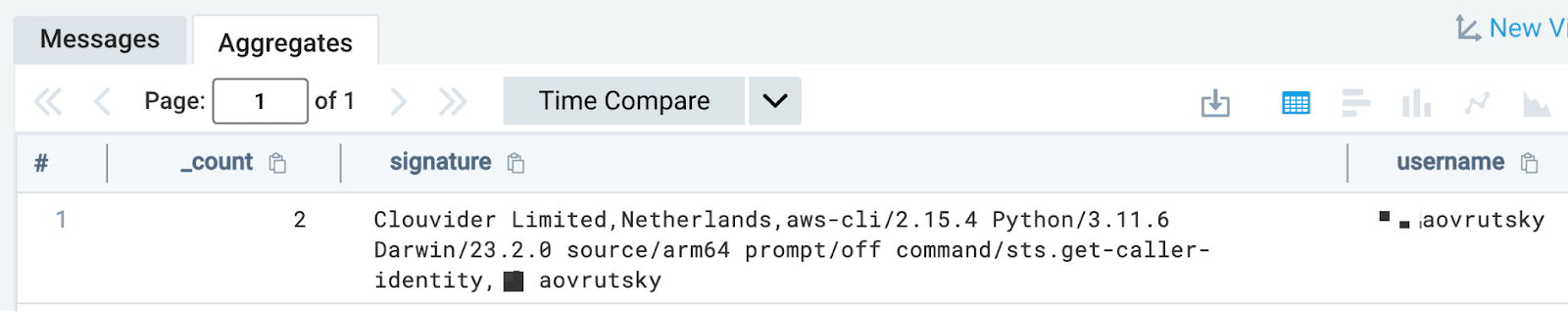

Looking at the results, we see that out of all the various session profile combinations, one is flagged as being significantly different from the rest:

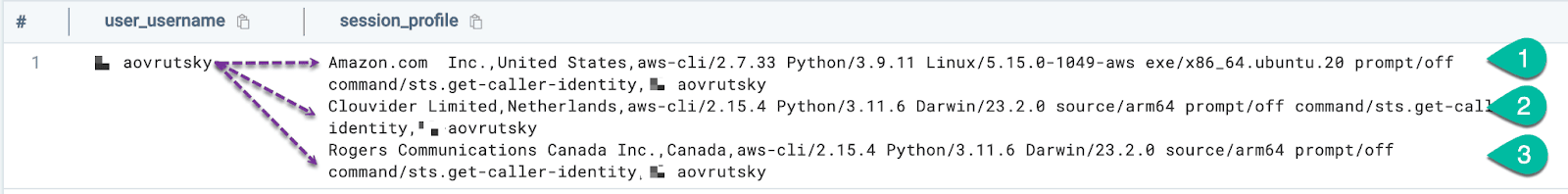

We can then pull on this thread a little bit and look at the session profiles in use by the user from the flagged entry:

_index=sec_record_audit

| where metadata_product = "CloudTrail"

| where !isBlank(user_username) and !isBlank(device_ip_asn)

| where user_username = "User" and !isBlank(session_profile)

| concat(device_ip_asn, ",", srcDevice_ip_countryCode, ",", http_userAgent) as session_profile

| values(session_profile) as session_profiles by user_usernameLooking at the results, we see three distinct session profiles in use:

Digging deeper into the data, we can see that the “Clouvider Limited” ASN, combined with access from an unusual country, is a strong indicator of a stolen session.

Conclusion

In this blog, we have highlighted some proactive threat-hunting hypotheses relating to cloud session anomalies. We have also provided some queries and rules that can be used to detect this activity in your environment.

To learn more about Sumo Logic Cloud SIEM, check out the product or click through an interactive demo.