Find threats: Cloud credential theft on Windows endpoints

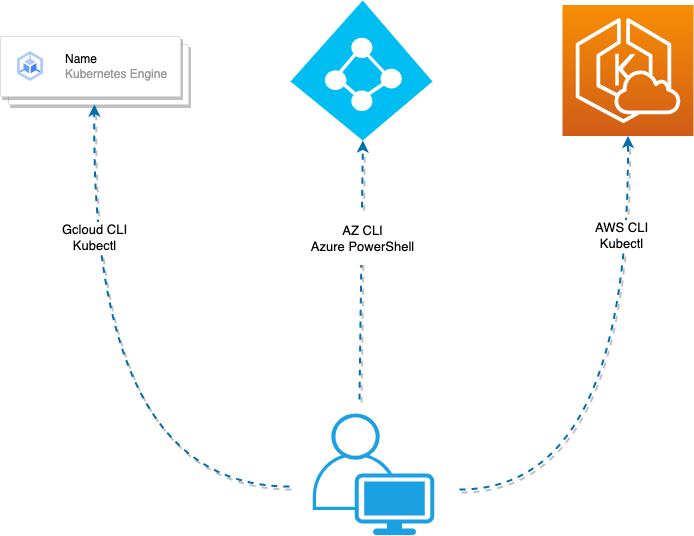

In today’s hybrid, multi-cloud environments, users and administrators connect to various cloud services using cloud-native tooling. This tooling, which includes command line utilities such as Azure CLI, AWS CLI, and Google Cloud SDK, stores authentication material on the local filesystem.

This post highlights the risks associated with unprotected and unmonitored cloud credentials which are found on these Windows endpoints.

Get actionable and direct guidance around:

- Data collection

- Baselining

- Hunting & Alerting

In order to alert on and hunt for this malicious activity.

Business workloads are increasingly undergoing a migration to the cloud. Indeed, business applications that are built on cloud infrastructure are becoming the norm rather than the exception.

Cloud migration inherently adds complexity, particularly as you’ll need to secure both the cloud environment and the on-premises endpoints that are used to manage cloud resources.

With this context as our backdrop, the Sumo Logic Threat Labs Team performs a deep dive into how cloud credential theft from Windows endpoints can be detected and hunted.

Threat model

Before diving into queries, data and hunts - let us take a step back and perform some threat modeling. This will help us understand the risks associated with cloud credential theft from Windows endpoints.

Here, we can use the OWASP threat modeling cheat sheet as a starting reference point.

A few key terms within OWASP’s threat modeling terminology are worth calling out specifically:

Impact: Cloud credential theft from an endpoint can potentially have an outsized impact. Consider the following scenario: An administrator has limited permissions on their Windows endpoint, but has elevated permissions in the cloud. If their cloud credentials are stolen, the threat actor can potentially access sensitive cloud resources that are otherwise out of reach.

Likelihood: The likelihood of cloud credential theft from endpoints is difficult to measure with accuracy, as it depends on a number of factors. However, credential access is a common tactic used by threat actors, and cloud credentials are an attractive target.

Controls: Controls are another aspect of our threat model which contains a large amount of variation. Several endpoint security products can detect and block credential theft, but the effectiveness of these controls varies.

Trust Boundary: According to OWASP, a trust boundary is: “a location on the data flow diagram where data changes its level of trust.”

The diagram below shows that the trust boundary is the endpoint, as the data - cloud credentials in this case - changes its level of trust when it is accessed by a threat actor.

We can imagine a scenario where the “trust” level differs between an endpoint and a cloud platform, and how stolen credentials can be used to access cloud resources.

Now that we have some introductory threat modeling notes, we are better positioned to understand the risks associated with cloud credential theft from Windows endpoints.

We also have a critical area to focus our detection engineering efforts on, as we know that the endpoint is the trust boundary.

Let’s continue, and look at some of the data required to hunt and alert on this activity.

Data tour - SACL auditing

Recalling our threat model, we have seen that cloud credentials found on a Windows endpoint reside primarily on the filesystem. This means that we need to monitor file access in order to detect credential theft.

As such, we will focus our attention on Event ID 4663 (An attempt was made to access an object.)

Enabling this event in a Windows environment is a two-step process:

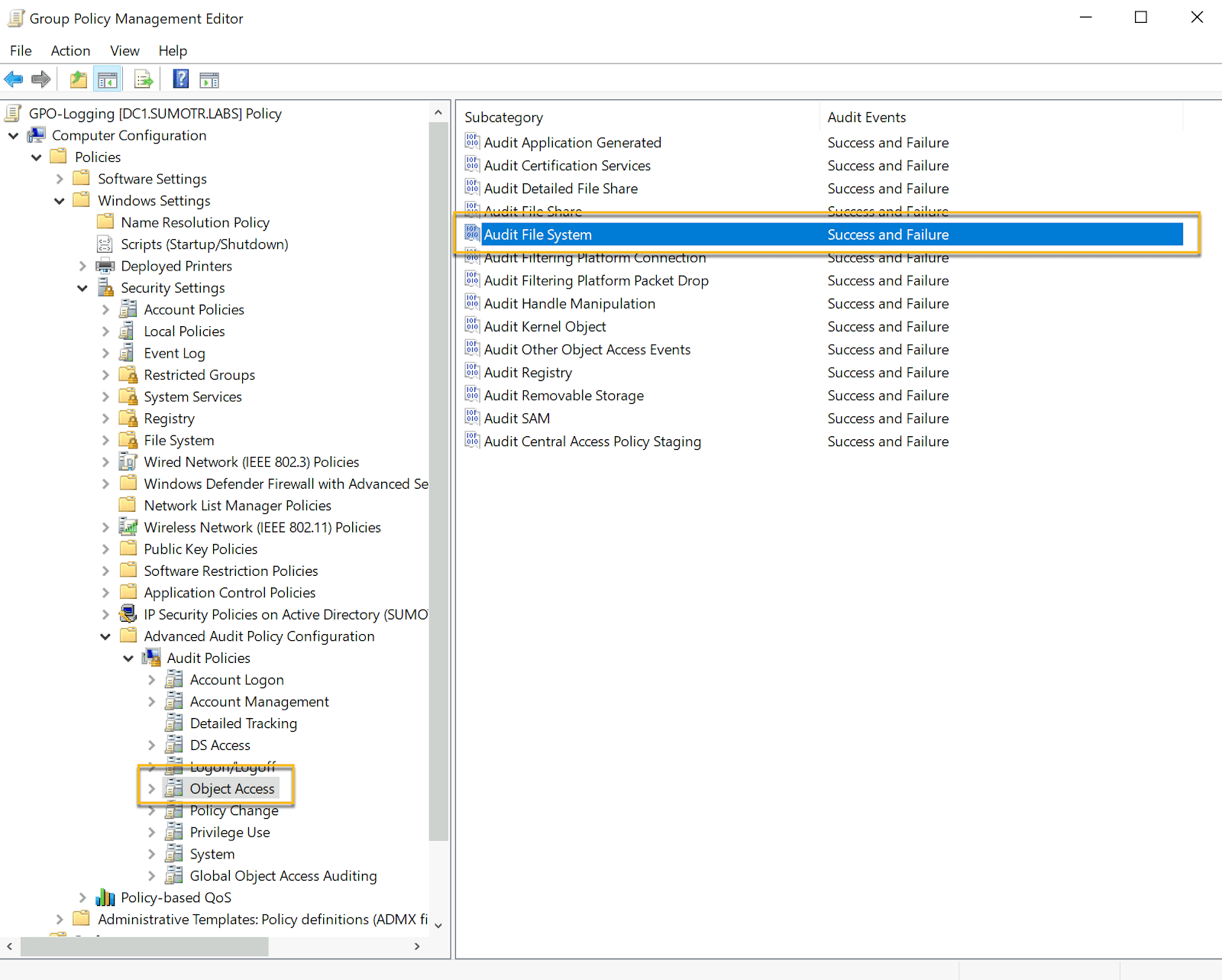

- The “Audit File System” setting needs to be enabled and applied to hosts on which cloud credentials reside.

- A system access control list (SACL) entry must be applied to each file that we wish to audit.

Enabling the “Audit File System” can be accomplished by navigating to:

Computer Configuration -> Policies -> Windows Settings -> Security Settings -> Advanced Audit Policy Configuration -> Object Access -> Audit File System

Once the “Audit File System” setting is enabled, we have to configure SACL auditing on each file we want to monitor.

Performing these steps manually per file would be a tedious process. Thankfully, researcher Roberto Rodriguez has done the heavy lifting and created a PowerShell script that automates this process.

You can find the script here.

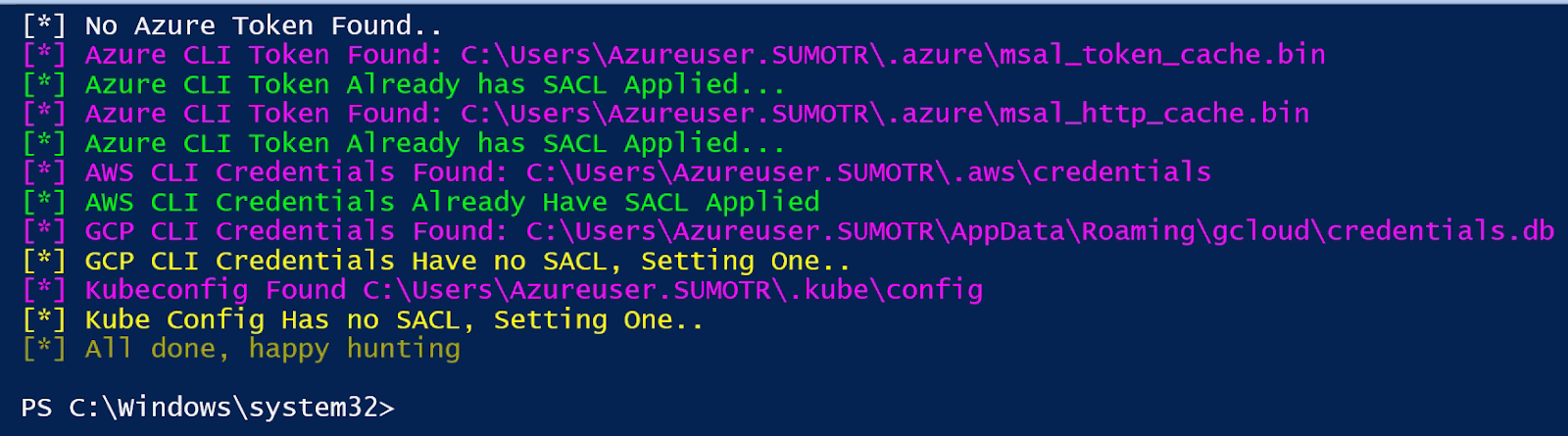

To further automate the setting of SACL entries on cloud credentials and keys specifically, the Sumo Logic Threat Labs team has created a wrapper script that uses the Set-AuditRule script to set SACL entries on common cloud credential locations.

The script makes all efforts to resolve paths dynamically. However, the locations of various cloud credential files may vary depending on the environment.

Please note that this script is provided as is and is not officially supported by the Sumo Logic team. Use at your own risk.

After running our wrapper script, we see the following output:

In this case:

- An Azure PowerShell token was not found, so no SACL was set

- Two Azure CLI Tokens were found which had SACLs applied already

- AWS CLI, Gcloud, and Kubeconfig credential files were located, with SACL auditing applied

Let’s take a step back to untangle some potentially confusing terminology around various Azure and AWS tokens and credentials.

In the context of this blog, we are examining potentially malicious access to an Azure Access Token, not a Primary Refresh Token (PRT).

PRT tokens can bypass conditional access policies and other controls if the target endpoint is joined to Azure AD. This is a more advanced attack vector that is outside the scope of this blog.

For more information regarding Azure PRT tokens, check out the following blogs and posts:

- The Office 365 Blog

- Microsoft Documentation regarding Primary Refresh Tokens

- A post by Dirk-jan Mollema on abusing Azure Primary Refresh Tokens

- A post by Thomas Naunheim on abusing and replaying Azure AD refresh tokens on macOS

- A post by InverseCos on Skeleton Keys and Pass-Through authentication

In contrast to PRT tokens, Azure Access Tokens are used primarily by those who wish to perform some kind of action against the Azure Resource Manager API or other Azure resources.

A way of thinking about this distinction is that Azure PRT tokens are primarily used to access various Microsoft 365 applications, while Azure Access Tokens are used to interact with Azure resources programmatically.

Data tour - file share auditing

As we have observed, various cloud service credential material can be found on an endpoints’ file system.

Likewise, you can also find cloud credential material on various file shares.

Similar to file system auditing, file share auditing also requires multiple group policy objects to be configured.

The first step is enabling the “Audit File Share” and “Audit Detailed File Share” settings.

You can find these in:

Computer Configuration -> Policies -> Windows Settings -> Security Settings -> Advanced Audit Policy Configuration -> Object Access -> Audit File Share

Computer Configuration -> Policies -> Windows Settings -> Security Settings -> Advanced Audit Policy Configuration -> Object Access -> Audit Detailed File Share

Enabling these two settings will generate a few new Event IDs, with two of particular interest for our hunting purposes:

Event IDs 5145 and 5140 will give us insight into what user accessed what share on our network. However, unlike SACL auditing, we do not need to configure per-file auditing.

There may be some confusion regarding which host generates the relevant event IDs: these will be generated on the host that is hosting the share, not the host that is accessing the share.

Having covered the telemetry required for monitoring files on both file shares and endpoints, let us now look at some baselining strategies.

Baselining SACL auditing activity

Now that we have the necessary configurations to enable SACL auditing, in addition to this auditing being applied to sensitive cloud credential files, we can start to baseline the activity.

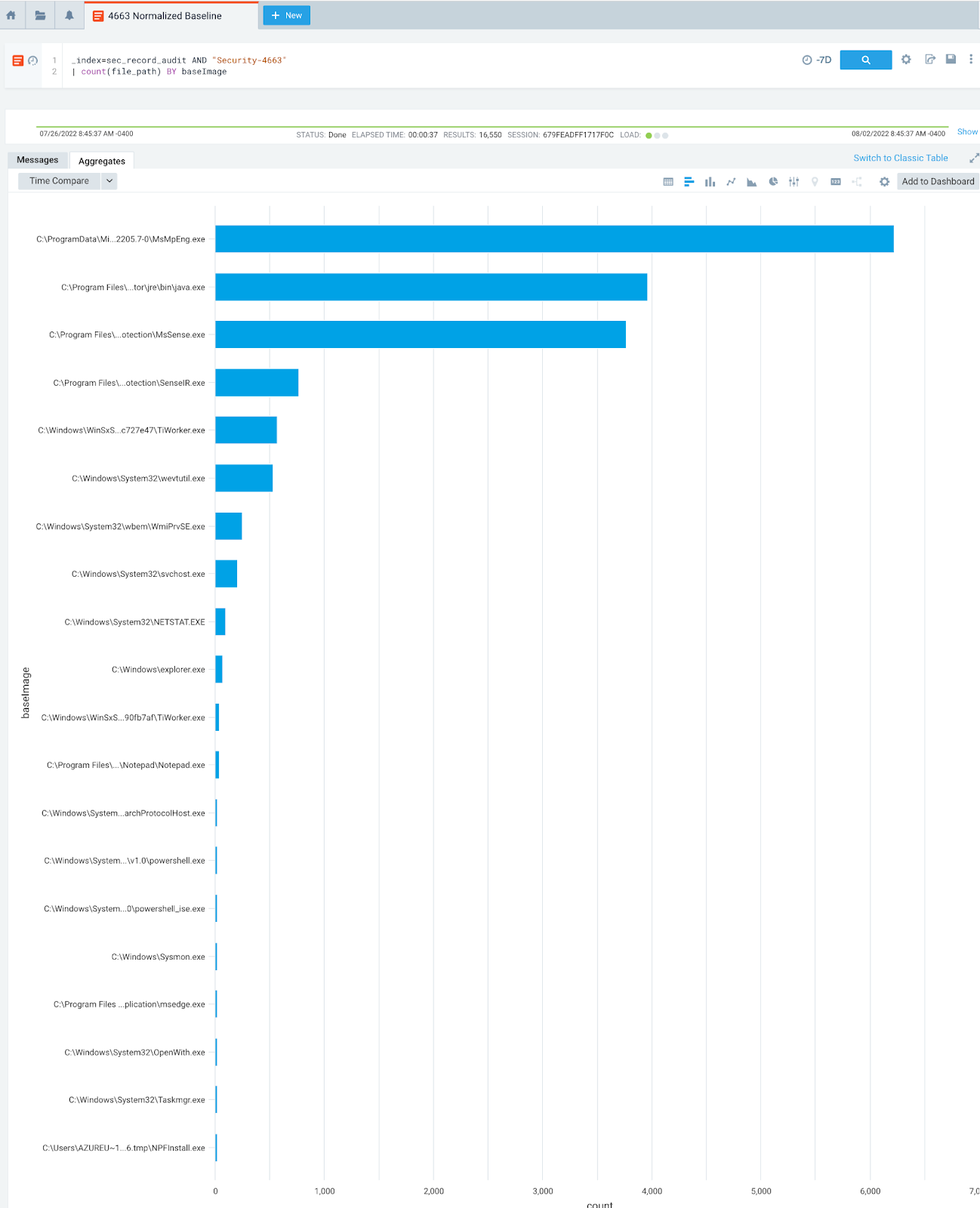

Let’s start with a relatively simple query:

_index=sec_record_audit AND "Security-4663"

| count(file_path) BY baseImageTo break this down, we are:

- Looking for Event ID 4663 only

- Counting the number of times a particular process accessed a particular object

In this case, an object can be a file, another process or an Active Directory Object.

Our objective for these baselining efforts is to see the types of data our 4663 events generate.

In other words, if we know what normal activity looks like on our endpoints, we will be better equipped to identify abnormal or malicious activity.

To examine some potentially abnormal events, we have gone ahead and opened all the monitored credential files with Notepad, simulating a threat actor reading the contents of these files.

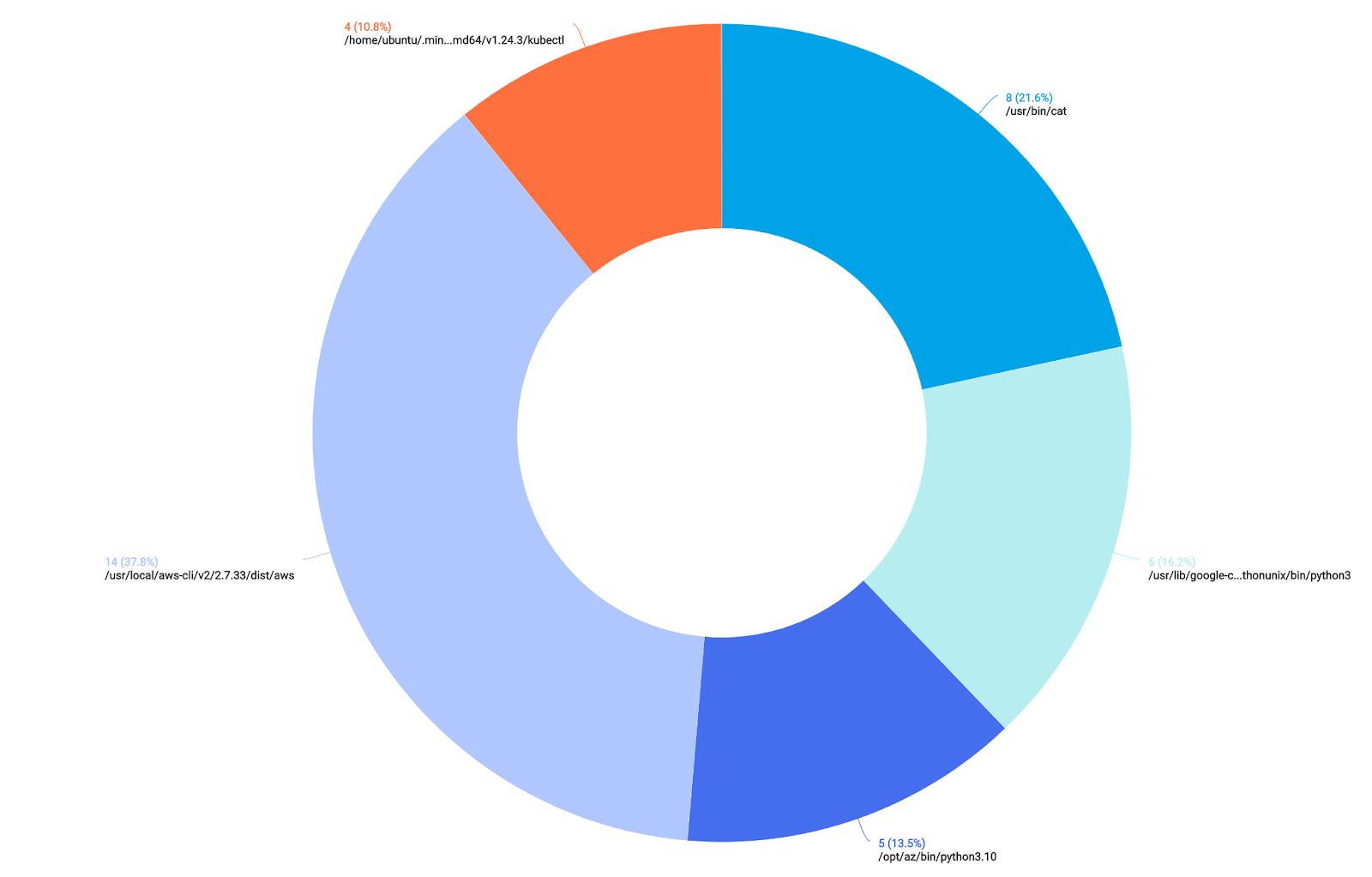

Let’s take a look at the results:

Perhaps not surprisingly, we can see that Windows Defender, Java and System processes are creating some noise in our data.

After some whittling down and filtering of our events, we end up with the following, much more focused data:

We see the first process on our list, which is our “control” - opening our cloud credentials with Notepad.

We expect to see the bottom two processes, as many of the CLI tools used to manage Azure, GCP and AWS resources are written in Python.

Baselining file share activity

Similar to SACL baselining, we also need to baseline our file share activity.

We can start with the following query:

_index=sec_record_audit AND "Security-5145"

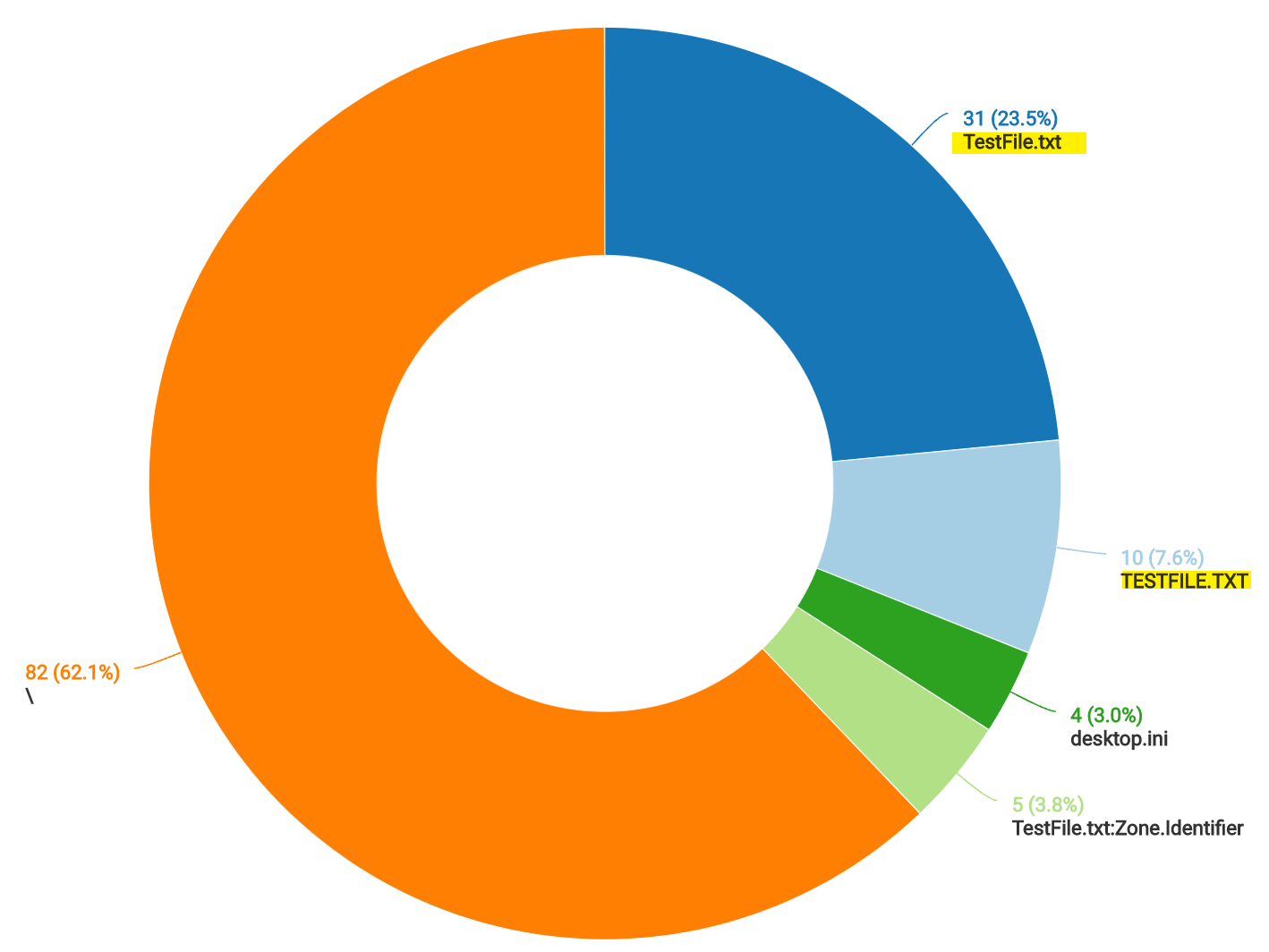

| count(file_path) as File BY file_basenameAfter our results are returned, we can view them in a pie chart:

We can see a lot of noise for group policy objects, as well as some activity (on the right-hand side of the chart) for PowerShell Transcription logs.

After a few exclusions of noisier events, we rerun our query and come back with the following results:

At this point, we have visibility into file access for critical cloud credentials found on our endpoints and file shares.

We have also completed some baselining of activity, which should make spotting anomalous or malicious activity much easier.

Hunting

To sum up where we are in our cloud credential hunting journey, so far, we have:

- Articulated a threat to our environment

- Configured the required data sources

- Baselined activity on our endpoints and file shares

Now, we can move towards hunting suspicious or malicious cloud credential access.

Cloud credential access on the endpoint

Since we have already undertaken baselining efforts, we should know what processes access sensitive cloud credentials on our endpoints.

Let us look at the following query:

_index=sec_record_audit

| where %"fields.EventID" matches "4663" and file_path matches /(.azure\msal_|.aws\credentials|\gcloud\credentials.db|.kube\config)/

| count by baseImage, file_pathIn this query, we are looking for what processes access sensitive credential files on our endpoint. We are using a regular expression to filter on the file paths that we know contain cloud credentials.

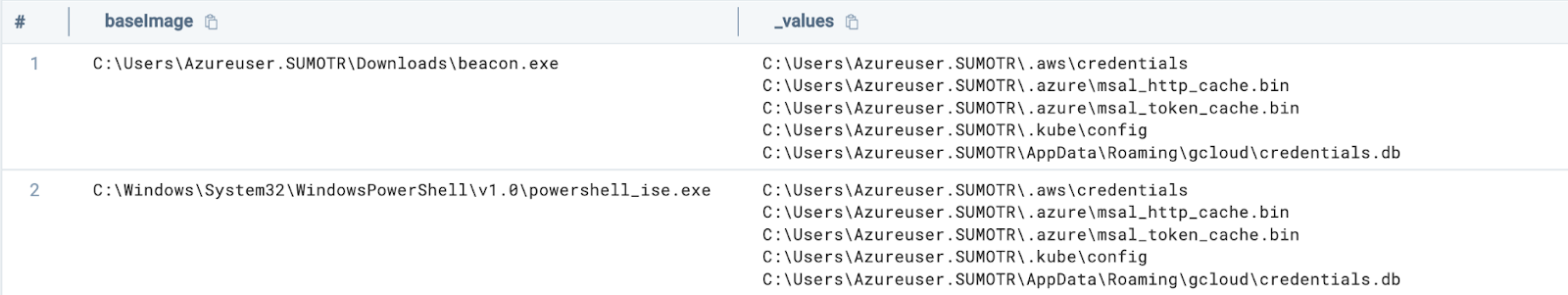

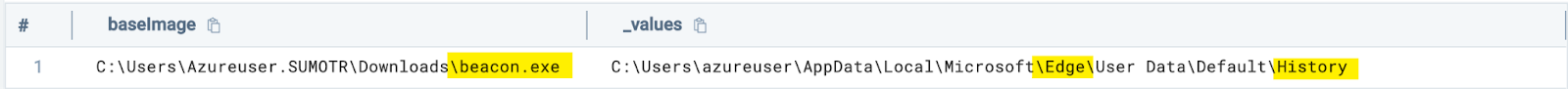

Looking at our results, we see the following:

On row one we see a suspicious process named “beacon.exe” accessing our cloud credentials.

However, on row two we see a seemingly legitimate PowerShell process accessing the same set of credentials.

This dynamic highlights the limitations of using a singular event or data point to make a determination of malicious activity.

Although the query above is an excellent start when hunting for malicious cloud credential use, we need to add additional context to our query.

From our baselining efforts, we know that the PowerShell process accesses our sensitive cloud credentials. However, we also know that PowerShell can be used for malicious purposes.

Some of the factors that we can use, using Sysmon or EDR data, combined with our newly configured SACL auditing, to determine if the PowerShell process is malicious include:

- Whether the PowerShell process was launched with a long and abnormal command line

- Whether the PowerShell process made multiple outbound network connections

- Whether the outbound network connection was to a public IP address

- Whether the PowerShell process did all the above while accessing our sensitive cloud credentials

In query form, this looks like:

(_index=sec_record_network OR _index=sec_record_endpoint OR _index=sec_record_audit) (metadata_deviceEventId="Sysmon-1" OR metadata_deviceEventId="Sysmon-3" OR metadata_deviceEventId="Security-4663")

| where baseImage contains "powershell"

| timeslice 1h

| 0 as score

| "" as messageQualifiers

| if(%"fields.EventData.Initiated" matches "true",1,0) as connection_initiated

| total connection_initiated as total_connections by %"fields.EventData.ProcessGuid"

| length(commandLine) as commandLineLength

| if (total_connections > 3, concat(messageQualifiers, "High Connection Count for PowerShell Process: ", total_connections, "\n# score: 10000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers

| if (!isBlank(dstDevice_ip_asnOrg), concat(messageQualifiers, "Powershell Connection to Public IP: ", dstDevice_ip, "\n# score: 10000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers1

| if (connection_initiated =1, concat(messageQualifiers, "PowerShell Outgoing Network Connection: ", dstDevice_ip, "\n# score: 10000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers2

| if (commandLineLength > 6000, concat(messageQualifiers, "Long PowerShell CommandLine Found: ", commandLine, "\n# score: 10000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers3

| if (file_path matches /(.azure\msal_|.aws\credentials|\gcloud\credentials.db|.kube\config)/,concat(messageQualifiers, "Cloud Credential File Accessed: ", file_path, "\n# score: 10000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers4

| concat(messageQualifiers,messageQualifiers1,messageQualifiers2,messageQualifiers3,messageQualifiers4) as q

| parse regex field=q "score:\s(?<score>-?\d+)" multi

| where !isEmpty(q)

| values(q) as qualifiers,sum(score) as score by _sourcehost,_timeslice

| where score > 40000To break this query down, we are:

- Looking at Event IDs 4663 (SACL Auditing), 4688/Sysmon EID1 (Process Creations), Sysmon EID3 (Network Connections)

- Looking at the PowerShell process only

- Time slicing our data in one hour chunks

- Checking to see if a particular connection was inbound or outbound

- Counting the total number of connections a particular PowerShell process made

- Setting qualifiers if:

- The total number of connections PowerShell made was greater than three (3)

- If an ASN is present, considering the connection to be made to a public IP address

- A connection was outbound

- The command line used for the PowerShell process is abnormally long

- The PowerShell process accessed our sensitive cloud credentials

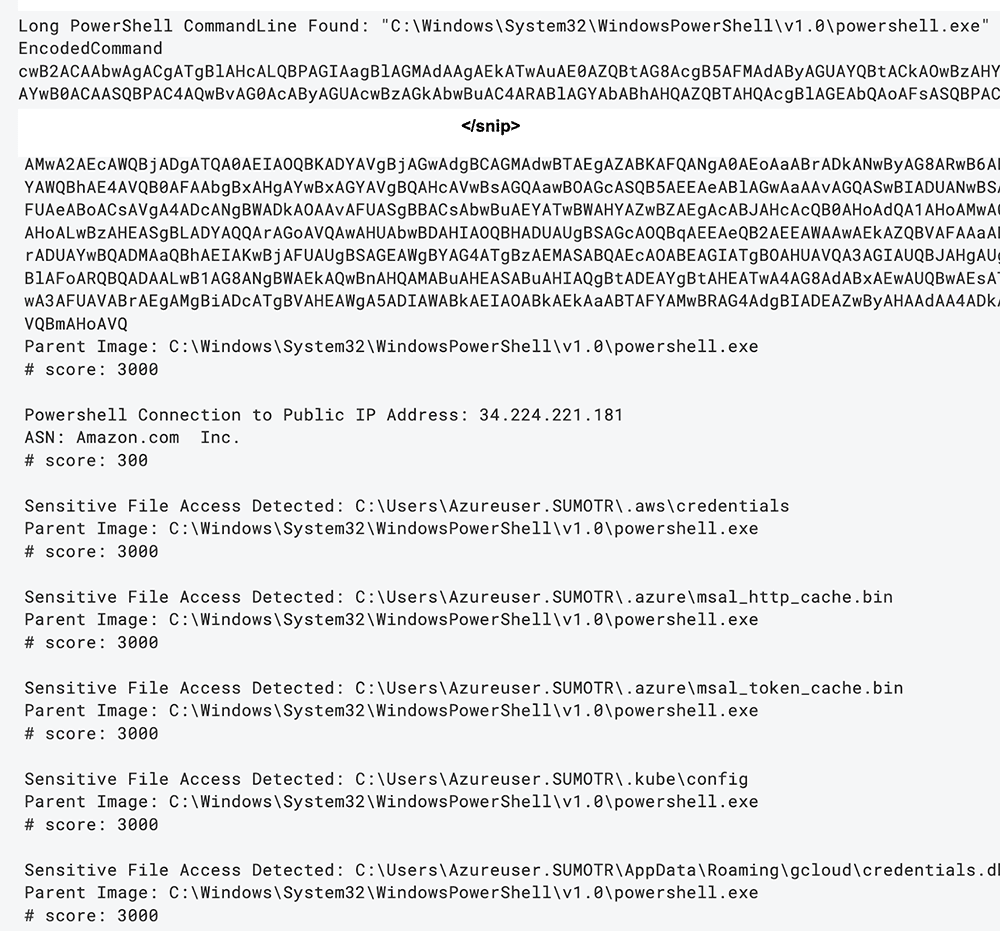

And looking at our results:

We can see our abnormally long and malicious command line (which was snipped for readability), as well as the other qualifiers that we set.

This additional context assists us in determining whether cloud credential access was normal behavior or malicious activity.

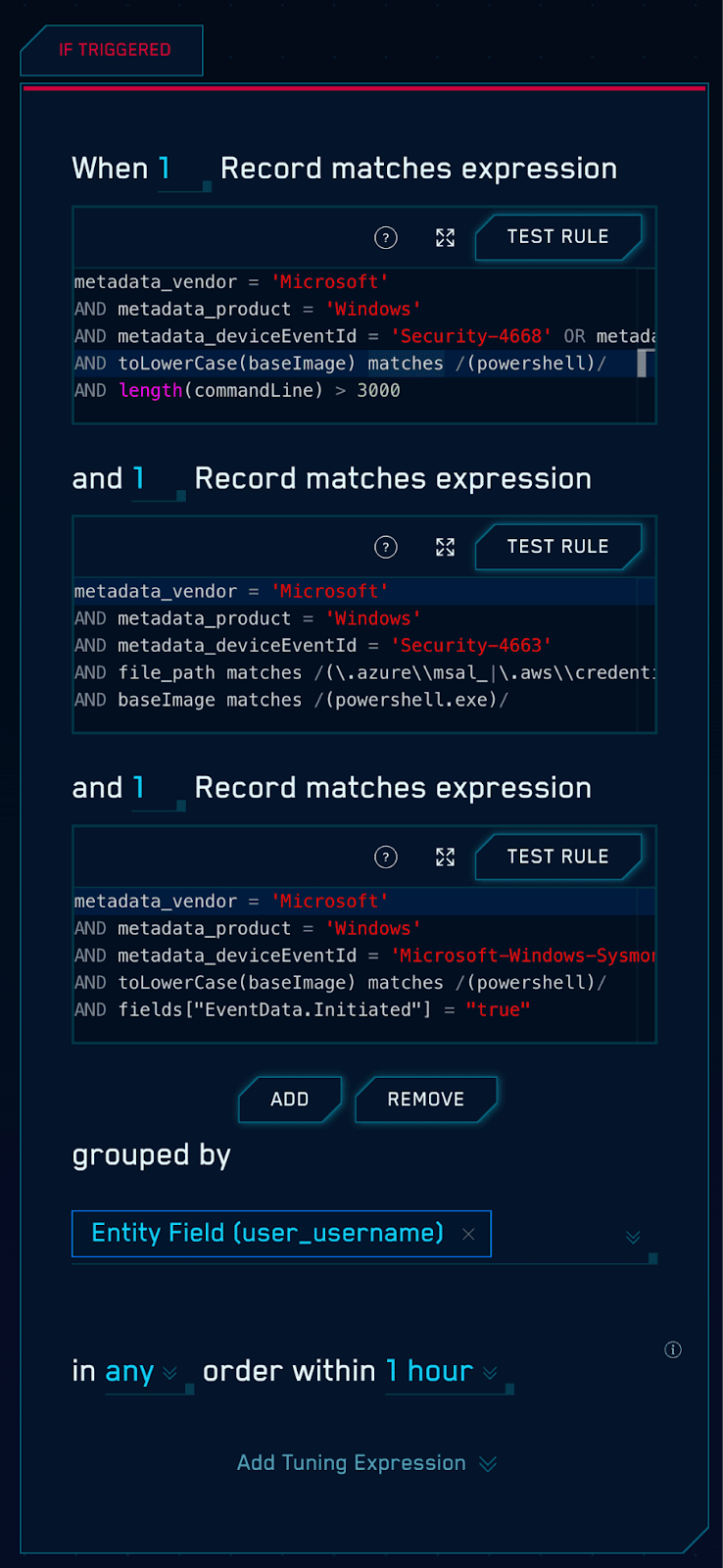

We can also utilize Sumo Logic’s Chain rule capability to build rule logic that looks for:

- A long PowerShell command line

- PowerShell establishing an outbound network connection

- PowerShell accessing our sensitive cloud credentials

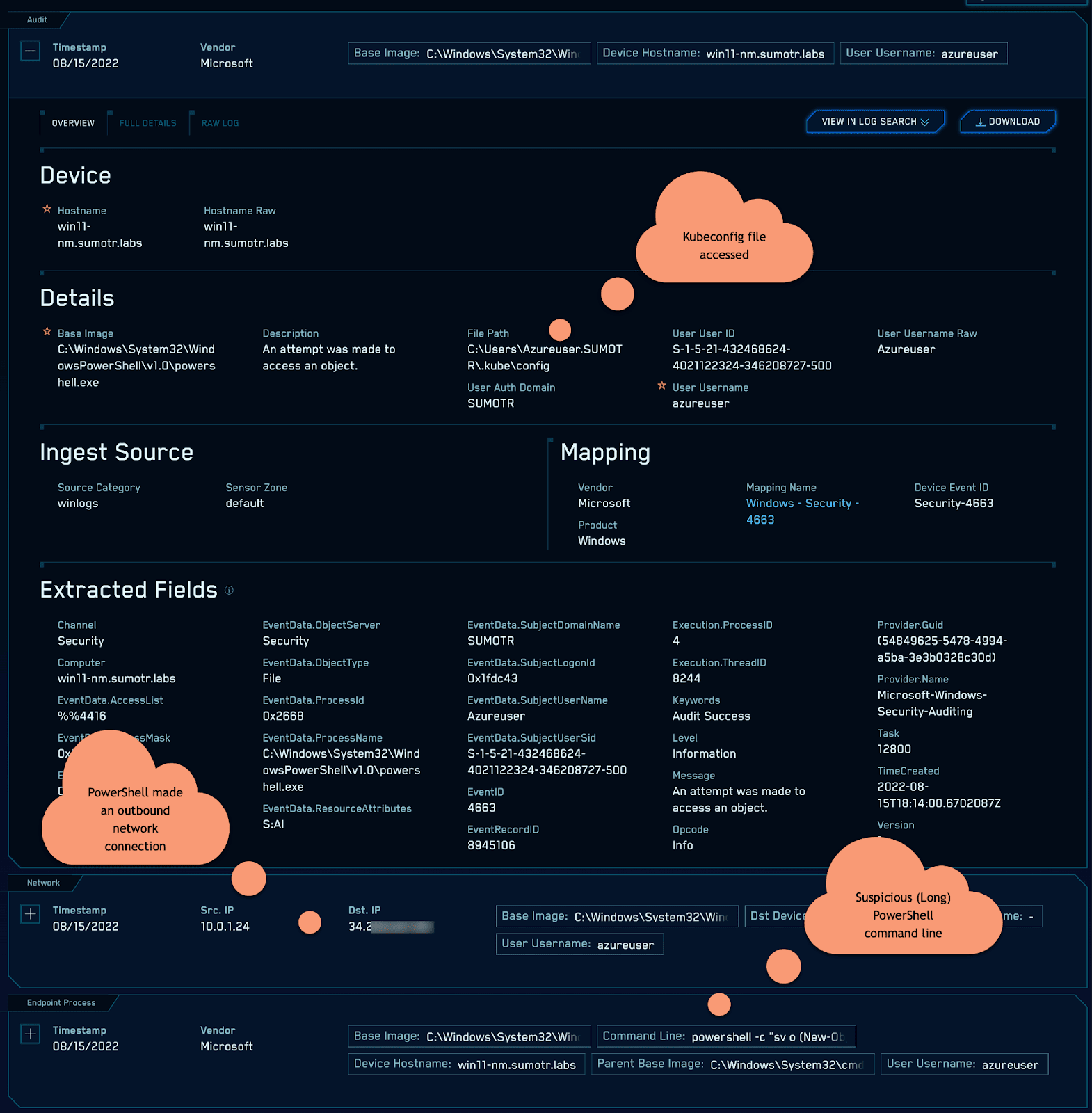

And looking at the results, we see an attack chain beginning to come into focus:

As we have highlighted, potentially sensitive credentials which grant access to cloud resources can be found on endpoints.

Keeping an eye on the browser

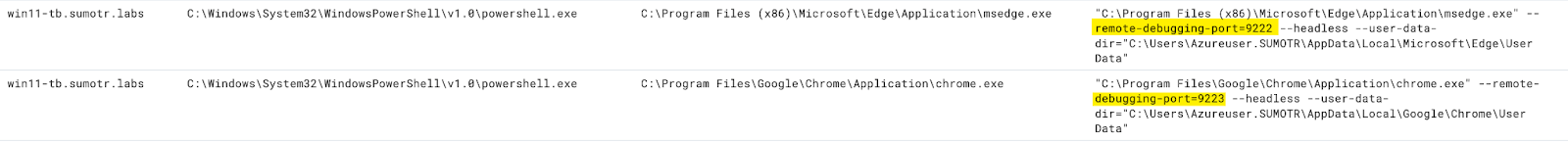

Tools like WhiteChocolateMacademiaNut by Justin Bui can connect to a Chromium browser’s remote debugging port in order to dump cookies or other sensitive information.

For this tool to function, Chrome or Edge need to start with a remote debugging port enabled.

We can hunt for this activity on our endpoints with the following query:

_index=sec_record_endpoint

| where toLowerCase(commandLine) contains "--remote-debugging-port" and toLowerCase(baseImage) contains any("chrome", "msedge")And looking at the results, we can see our Chrome and Edge processes started with a remote debugging port enabled:

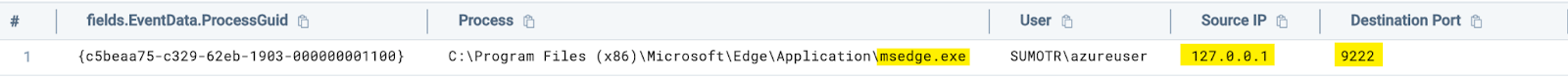

If Sysmon is available in the environment, or if your EDR can be instrumented with custom rules, another detection opportunity exists in looking at incoming connections to Chrome or Edge processes.

The following Sysmon rule snippet will capture incoming connections to Edge or Chrome over loopback addresses. This can help detect tunneling techniques as well.

<Rule name="Chromium Incoming Network Connect" groupRelation="and">

<Image condition="contains any">msedge;chrome</Image>

<Initiated condition="is">false</Initiated>

<SourceIp condition="contains any">127.0.0.1;0:0:0:0:0:0:0:1</SourceIp>

</Rule>After gaining the relevant telemetry, we can query for this data with the following:

_index=sec_record_network and metadata_deviceEventId="Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon/Operational-3"

| where toLowerCase(baseImage) contains any("chrome", "msedge") and srcDevice_ip matches /127.0.0.1|::1/And looking at our results, we can see the following:

Apart from cookie theft, system enumeration / situational awareness tools like SeatBelt often enumerate browser history and other sensitive data.

We can detect this enumeration activity by setting SACL entries on sensitive browser files.

Let’s look at the following query, which looks at what processes are accessing Edge or Chrome’s history files:

_index=sec_record_audit and metadata_deviceEventId="Security-4663"

| where file_path matches /(Microsoft\\Edge\\User Data|Google\\Chrome\\User Data)/ and file_basename = "History"And looking at our results, we see our fictitious “beacon.exe” process accessing the history file of both Chrome and Edge:

Cloud credential access in file shares

Consider the following scenario: a cloud Administrator stores SSH keys on a file share. These SSH keys are used to access cloud virtual machines.

A threat actor compromises a machine of a user with access to the file share, but not to the organization’s cloud infrastructure.

The threat actor locates the SSH keys saved to an unprotected file share, and proceeds to utilize them to access the organization’s cloud infrastructure.

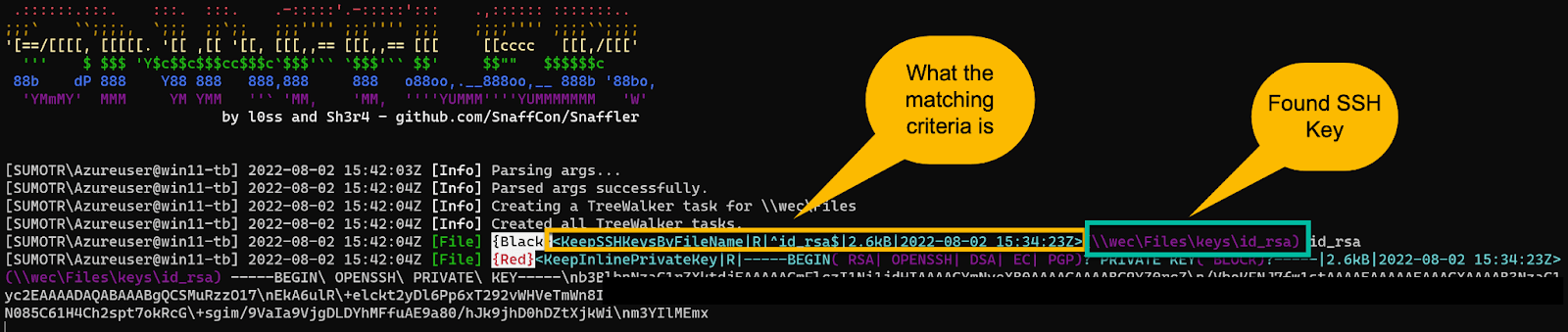

You can use tools like Snaffler by l0ss and sh3r4_hax to find these sensitive files:

We can take several hunting approaches to locate this activity on our network.

Let’s start with a basic example, looking for a larger than normal amount of failed requests to file shares.

This scenario assumes that the threat actor is scanning activities on a large number or all of the file shares on the network.

The account utilized to scan these file shares may not have the necessary permissions for every file share, resulting in failed access attempts.

Let’s take a look at the following query, which attempts to capture this activity:

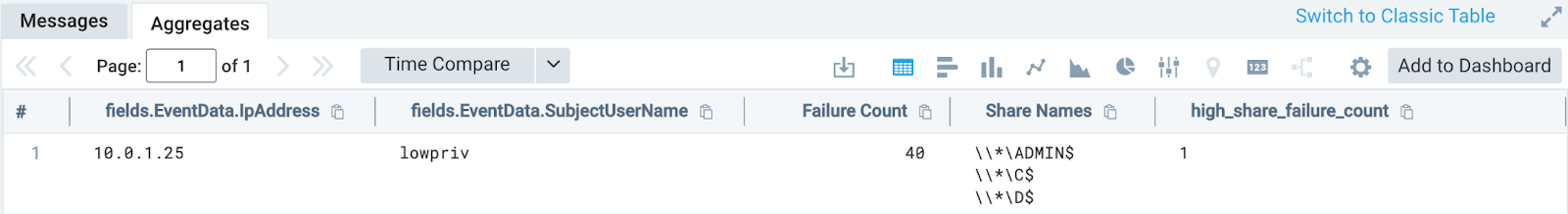

(_index=sec_record_audit AND "Security-5140") AND !"Audit Success"

| count (%"fields.EventData.ShareName") as share_count by %"fields.EventData.IpAddress", user_username

| if(share_count > 20, "high_share_failure_count", "normal") as share_access_statusBreaking this query down, we are:

- Looking for Event ID 5140 in the normalized index

- Filtering the results by Audit Failure only

- Counting the number of failed share access requests by a certain IP address & user name

- Using an IF statement to set a field called “high_share_failure_count” if the number of failed share access requests is greater than 20

Looking at our results, we see the following:

In our case, the user “lowpriv”, coming from the IP address of “10.0.1.25” failed to access forty (40) different shares.

With this query, we now know that someone in our network is scanning file shares and does not have access to all of them.

This is great visibility to have, but the above hunt lacks contextualization.

For example, we don’t know if sensitive files were accessed and we do not have a good way of excluding legitimate activity.

With this in mind, let’s add some color to our query and add some additional qualifiers, such as sensitive file access:

_index=sec_record_audit AND ("Security-5140" OR "Security-4663")

| where !(%"fields.task" matches "*12802*")

| where !(file_path matches "*\REGISTRY\MACHINE*")

| where !(file_path matches "*\*\SYSVOL*")

| where !(resource matches "\\*\SYSVOL*")

| timeslice 1h

| 0 as score

| "" as messageQualifiers

| "" as messageQualifiers1

| if(%"fields.keywords" matches "*Audit Failure*", 1,0) as share_failure

| if(%"fields.keywords" matches "*Audit Success*", 1,0) as share_success

| total share_failure as share_access_fail_count by %"fields.EventData.IpAddress"

| total share_success as share_access_success_count by %"fields.EventData.IpAddress"

| if (share_access_fail_count > 20, concat(messageQualifiers, "High Share Fail Count: ",share_access_fail_count,"\n# score: 1000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers

| file_path matches "*id_rsa*" as sensitiveFileAccess

| if (sensitiveFileAccess, concat(messageQualifiers, "Sensitive File Access: ",file_path,"\nUsername:",user_username,"\n# score: 3000\n"), messageQualifiers) as messageQualifiers1

| concat(messageQualifiers,messageQualifiers1) as q

| parse regex field=q "score:\s(?<score>-?\d+)" multi

| where !isEmpty(q)

| values(q) as qualifiers,sum(score) as score by _timeslice

| where score > 3000We:

- Look at event codes 4663 and 5140

- Exclude some noisy events

- Set a time window of one hour

- Tabulate the amount of failed and successful share access events per IP address

- Add logic to determine if the amount of failed shares is considered “high”

- Add logic to determine if a sensitive file has been accessed

- Add a score if the number of failed share access events was high

- Add a score if a sensitive file was accessed

- Sum up the score and present the data

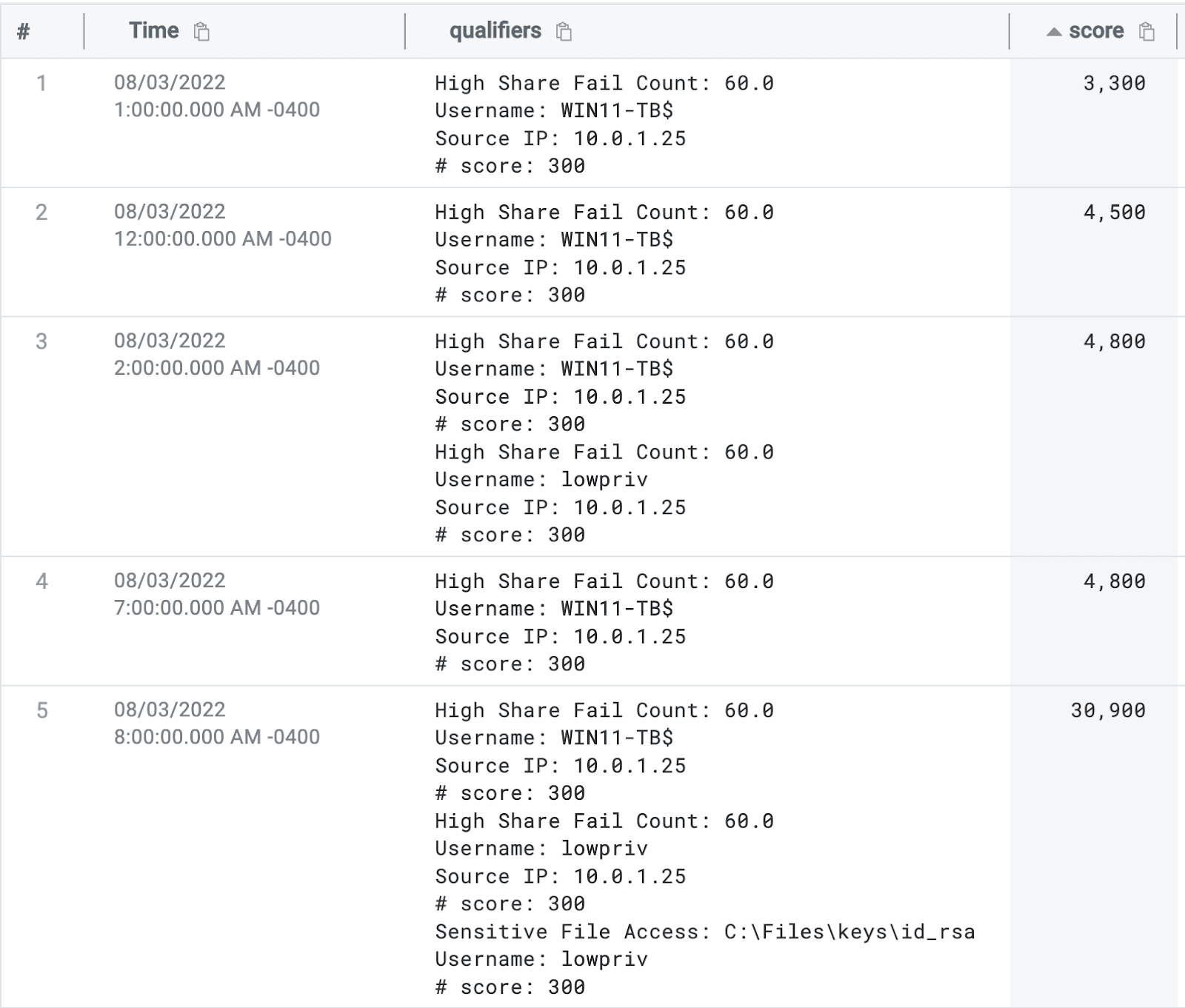

Looking at the results of our query, we can see the following:

We notice the machine account “WIN11-TB$” failing to access some shares on rows one and two, which triggers one of our qualifiers.

On rows three and four, we also see the machine account and a user account triggering our qualifiers as well as our sensitive file access qualifier.

The fictitious scenario outlined above lends itself well to qualifier or score-based queries and hunts.

We can see our “legitimate” activity taking place on rows 1-4 with a score of about 4,800 - however, on rows 5-7 we can see our malicious activity with a much higher score.

We can then add a “where” statement to our query to only return results if the score is higher than a certain value.

Hunting in file share and file access Windows events is tricky. Several factors work against us, including:

- The interplay between NTFS and file share permissions and their disparate set of telemetry

- The general “background noise” of various network and endpoint scanning appliances

- Lack of visibility and intelligence regarding where sensitive files are located on shares

- Overly-permissive file share access

- Verbose and voluminous SACL and file share events

However, this visibility and monitoring gap can be closed with a tactical focus and the right hunting strategies.

Final thoughts

Cloud credentials on the filesystem, in network shares and in browser cookies represent an attractive target for threat actors.

This blog post has highlighted this potentially impactful threat vector. We hope that organizations can use this guidance to detect and respond to cloud credential theft on Windows endpoints.

CSE Rules

The threat labs team has developed and deployed the following rules for Cloud SIEM Enterprise customers.

| Rule ID | Rule Name |

|---|---|

| THRESHOLD-S00059 | Network Share Scan |

| MATCH-S00820 | Cloud Credential File Accessed |

| MATCH-S00819 | Chromium Process Started With Debugging Port |

| MATCH-S00821 | Suspicious Chromium Browser History Access |

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

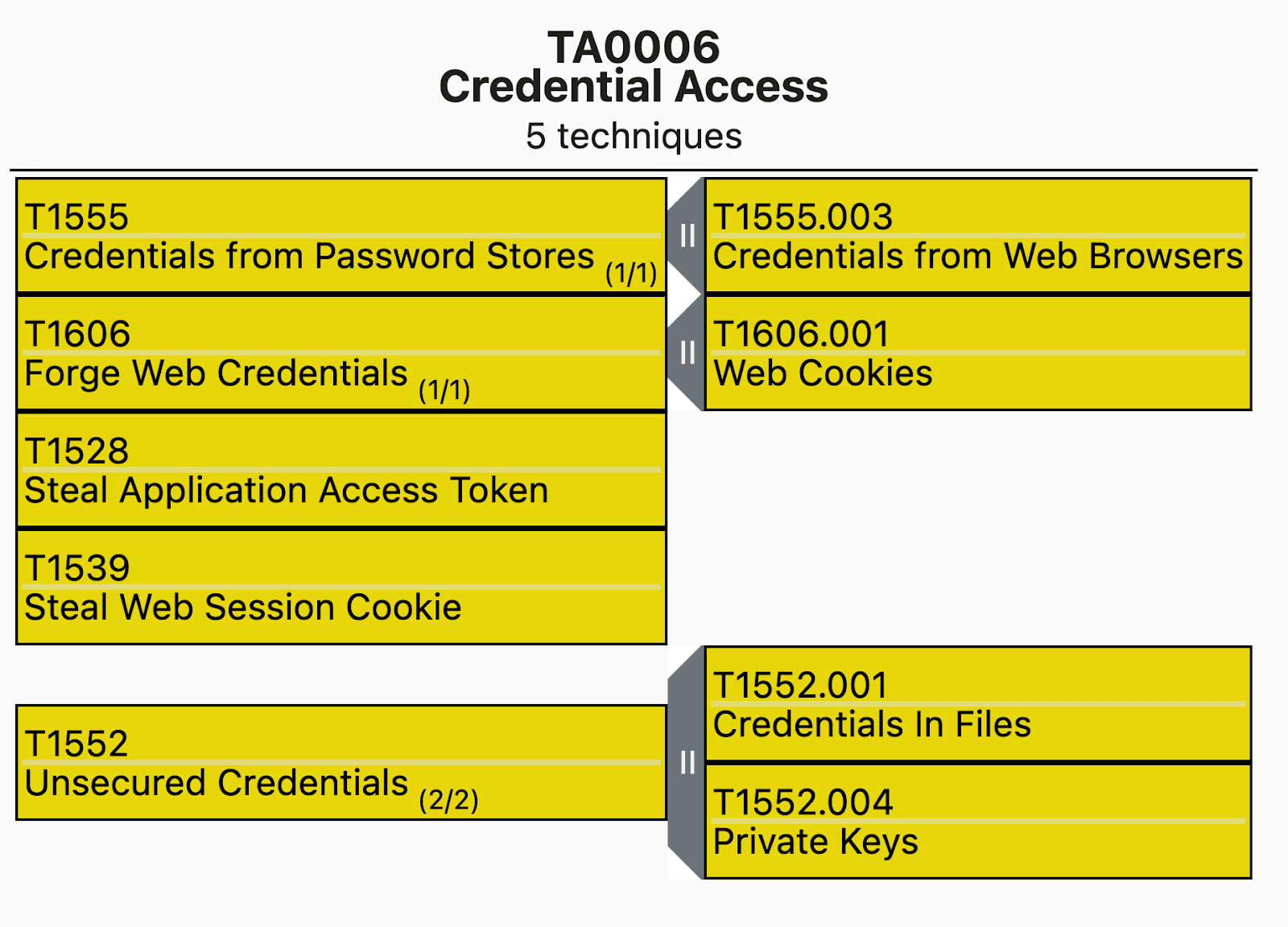

In terms of MITRE ATT&CK Mappings, the following MITRE IDs make up the bulk of the techniques which are covered by this blog:

References

- https://medium.com/@cryps1s/detecting-windows-endpoint-compromise-with-sacls-cd748e10950

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/security/threat-protection/auditing/apply-a-basic-audit-policy-on-a-file-or-folder

- https://github.com/rootsecdev/Azure-Red-Team#stealing-tokens

- https://mikhail.io/2019/07/how-azure-cli-manages-access-tokens/

- https://github.com/secureworks/family-of-client-ids-research

- https://azurelessons.com/azure-powershell-vs-azure-cli/

- https://www.lares.com/blog/hunting-azure-admins-for-vertical-escalation/

- https://www.lares.com/blog/hunting-azure-admins-for-vertical-escalation-part-2/

- https://github.com/slyd0g/WhiteChocolateMacademiaNut

- https://github.com/OTRF/Set-AuditRule